In the opening scene of Steven Spielberg’s Raiders of the Lost Ark, Indiana Jones attempts to disarm a booby-trapped altar at the heart of a temple in the Peruvian Amazon to loot a pre-Columbian artifact on a commission from the National Museum. Although there is no indication of the particular significance of the object or meanings attributed to it, the narrative structure—a classic projection of colonial desire marked by ethnocentric tropes—underscores the values the artifact embodies in the eyes of the cultural plunder. Cast in gold and depicting a nude fertility goddess in the act of childbirth, the artifact is framed as a menacing fetish; a treasure to be conquered and exhibited in a vitrine as evidence of the archeologist’s prowess over the primitive locals who intended, and failed, to protect it.

Since the premiere of the film in 1981, the fictitious artifact known as the Golden Idol has gained an iconic status amongst prop-enthusiasts. It is often alluded to as one of the most well-known props of cinema history. Beyond the value attributed to the object within the colonial diegetic space of the film, the resin prop has accrued enough monetary value to be at the center of auction sales, complete with disputes over the authenticity and provenance of its replicas. Such disputes appear untroubled by the fact that the original Golden Idol is itself a copy of an actual artifact in the pre-Colombian collection of the Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC.

An icon of pre-Columbian art, the original artifact has attracted the attention of scholars and collectors since it was first mentioned in an 1899 publication by the chief curator of the Trocadero Museum, Ernest-Théodore Hamy. Hamy—who, upon encountering the artifact in a Paris antiquities store and describing it as a “woman whose ethnic verity is completely gripping”—was the first to interpret it as a representation of the Aztec goddess, Tlazolteotl, also called Ixcuna.1 After passing through the hands of a number of antiquities dealers and integrating prestigious European collections, the artifact was purchased by Robert Woods Bliss in 1947 and has since been on exhibition as the Birthing Figure. While anthropologists have been able to retrace the provenance and social life of the artifact in Europe, it is still unclear under what circumstances it crossed the ocean.

The object also has a perennial presence in art history, having found particular resonance with the Surrealists, who often identified in ethnographic artifacts the uncanniness and potential for aesthetic disruption that guided their efforts. André Breton owned a ceramic copy of the artifact and, in the 1930s, Man Ray photographed the object for a photomontage titled Statuette of Ixcuina, Mexican Goddess of Maternity. The piece consists of four photographs of the artifact taken a few degrees apart along its axis of rotation and presented sequentially as stills of an animation. Eschewing the aesthetic conventions of traditional ethnographic photography, the montage suggests a rotational movement and imbues the still images with an entrancing sense of vitality often projected by Surrealists in non-Western cultures.

Since the 1960s, an increasing number of scholars began to challenge the Birthing Figure’s authenticity. The depiction of Tlazolteotl naked and unadorned was unlike any other carving of an Aztec deity and her expressive grimace and the virtuosic carving of her hair were considered anachronistic. In 2002, the anthropologist Jane MacLaren Walsh examined the piece to determine its authenticity and provenance. By making silicone impressions of the tool markings on the artifact and examining these under a scanning electron microscope, MacLaren Walsh confirmed that the tool marks could not have been achieved with pre-Columbian lapidary technology and that much of the carving was done using modern rotary tools.2

Although MacLaren Walsh was able to establish the inauthenticity of the artifact and trace its provenance to the Parisian shop where Hamy first encountered it, any information prior to this moment is mere speculation. The anthropologist suggests it might have been inspired by the Tlazolteotl figure painted in the Borbonicus Codex, even though in this depiction the goddess is covered by clothing, adorned with insignias and a neutral stance—no sign of a painful grimace in sight. Despite the conclusion, the museum continues to exhibit the sculpture, claiming that it has acquired a modern cultural identity that transcends “issues of origin and genuineness” and stands as an “icon of the ever-changing perceptions and connoisseurship in the field of pre-Columbian studies.”3

The museum’s response suggests that the authenticity of an artifact is not a given attribute to be assessed exclusively through objective research, but is instead predicated upon the artifact’s relationship to the museum. In fact, art historian Esther Pasztory states that the Birthing Figure was elevated to the level of an icon and masterpiece of pre-Columbian art, not for its authenticity, but because it presents a “barbaric splendor”—that is, it embodies the central elements of the Western taste for pre-Columbian art.4 In other words, the authenticity of the artifact is not measured according to its connection to an author, but conditional upon its ability to comport the projections and fantasies assigned to it by museum discourse and simultaneously reflect them back to the viewers.

Given that the Birthing Figure is now recognized as fictional as the Golden Idol, one could argue that one of the roles it plays within the museum discourse follows a representational logic not unlike that of Raiders of the Lost Ark. The copy, in both contexts, took precedence over its matrix to a degree that questions about the original are deemed secondary if not irrelevant. The acknowledgment of the derivative nature of both fictional artifacts appears to leave their distinct auras undiminished. In fact, Dumbarton Oaks perceives the reference to a Birthing Figure in Raiders as an event that reinforces the auratic status of the artifact.

While it seems irrefutable that the Birthing Figure was the referent for the Golden Idol, the assertion of its own referent remains ungraspable. Without a stable original, to designate the object merely as a fake seems insufficient and forecloses the disruptive potential it embodies as a real living memory, or an artifact, of the exotic roles projected on it. Suspended in a state of indeterminacy, the lost referent renders visible the representational conventions that are used to create the appearance of ethnographic truth in the theater of otherness. [seq_logo]

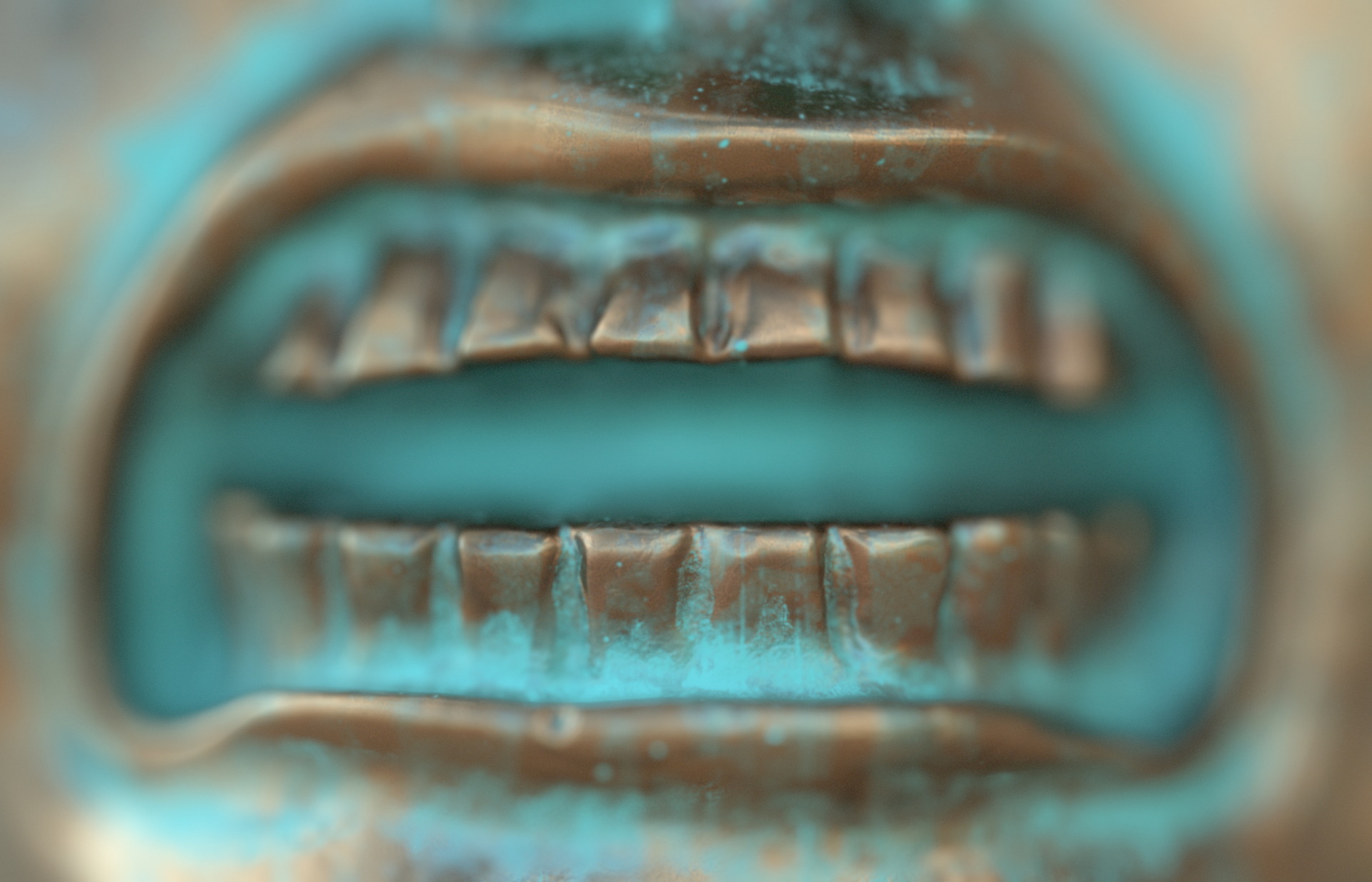

All images 3D rendered by the artist departing from a replica of the Golden Idol. Each reproduction of the artifact was rendered with custom made textures and materials. The replica is available for download and 3D printing.

1 Hamy, Ernest-Théodore. “Sur une statuette mexicaine de la déesse Ixcuina.” Journal de La Société Des Américanistes 3, no. 1 (1906): 1–5.

2 MacLaren Walsh, Jane. “The Dumbarton Oaks Tlazolteotl: Looking beneath the Surface.” Journal de La Société Des Américanistes 94, no. 94–1 (July 15, 2008): 7–43.

3 Archives, Dumbarton Oaks. “The Birthing Figure in the Robert Woods Bliss Collection of Pre-Columbian Art.” News Item. Dumbarton Oaks. Accessed December 10, 2020.

https://www.doaks.org/research/library-archives/dumbarton-oaks-archives/historical-records/75th-anniversary/blog/the-birthing-figure-in-the-robert-woods-bliss-collection-of-pre-columbian-art.

4 Pasztory, Esther. “Truth in Forgery.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 42 (2002): 159–65. Pasztory lays out six key qualities an artifact ought to have in order to embody the “barbaric splendor” historically sought after by Western taste: “1. Precious material; 2. Exquisite technical virtuosity despite use of stone tools; 3. Breathtaking naturalism; 4. A simultaneous simplification of form into abstraction that conveys the exotic; 5. A bizarre, grotesque, ugly, or bloody aspect that is a transgression of European norms; 6. Some kind of glyphic or structural complexity to be decoded.”

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTOR

Felipe Meres was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil in 1988 and currently lives and works in New York. His sculptures, films and photographs engage relationships between systems of representation and the material realities they intend to capture. Often exploring the limits of tools used to classify and organize aspects of the world in particular moments in history, Meres’ work invites the viewer to reconsider the patterns and forms we create to make sense of and regulate the objects, bodies and behaviors that surround us.

Solo exhibitions include The Telomeric Cut at Mendes Wood DM, São Paulo (2017) and Fsision at Company Gallery, NY (2016). His work has been shown in venues such as the Cuenca Biennial, Ecuador (2018); GAMeC, Italy (2018) and the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation, FL (2016). He was an artist in residency at Casa Wabi, Mexico (2018); ArtCenter/South Florida, FL (2016) and Escola de Verão, Capacete, Rio de Janeiro (2012). He holds an MFA from the Milton Avery School of the Arts at Bard College, NY and is a PhD Candidate in Anthropology at The New School, NY. He is the recipient of the 2016 Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation Grants & Commissions Award and of the 10th Tom of Finland Foundation Emerging Artist Grand Prize.