TRISTAN DUKE: TRANSITIONAL LENSES

Nor shapes of men nor beasts we ken—

The ice was all between.

—Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, 1834

•

Tristan Duke and I were on the road and required some supplies. I wanted chewing gum; he needed dry ice. The Smart & Final Extra!, a supermarket warehouse on Verdugo Road in Glendale, is one of the few retailers around Los Angeles where you can purchase the latter at dawn. (Danny Boy’s Ice Dock, under the Santa Monica Freeway near downtown, is another, and perhaps the only LA ice merchant willing to fill a truck bed with manufactured snow.)

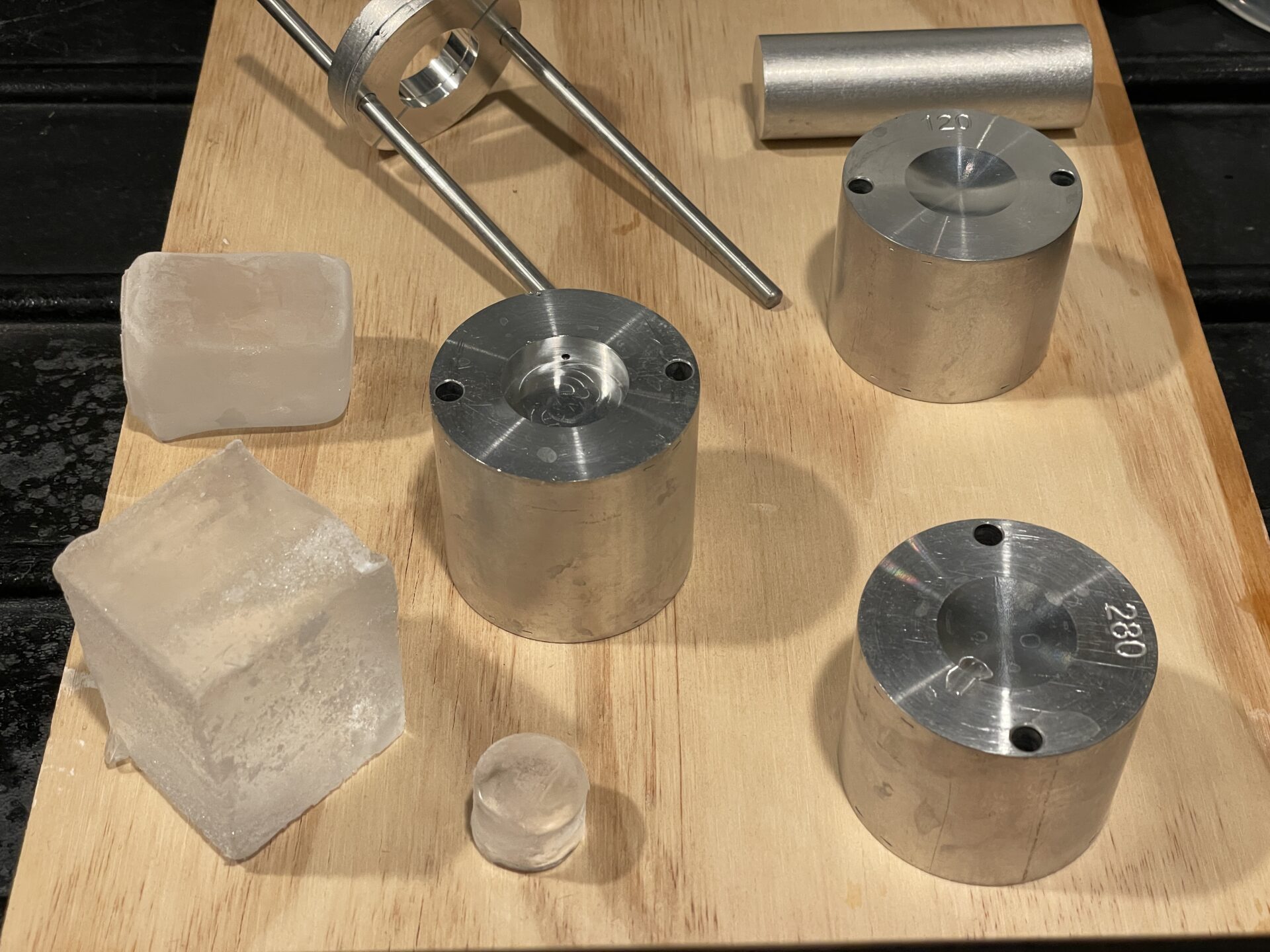

We found Penguin-brand dry ice in one-pound blocks, with the supplier’s phone number (1-887-PENGUIN) and website address printed on the wrapper. The company recommends using their product to pack freshly hunted game or transport breast milk. Duke used it to preserve his signature ice lenses, which are exactly that: photographic lenses fashioned from ice. The lenses are fragile and fleeting by design, so Duke must carefully stabilize them until their decisive moments arrive. In the parking lot, he removed a storage bag containing about a dozen ice cylinders from a cooler. The demitasse-sized plugs glowed dimly behind fogged plastic. Fitting them to the camera would come later; we had the first leg of a day’s journey to accomplish before any calibration would occur.

The milky sky and damp air forecasted coolness, finally, after too many too hot weeks confused an already subtle shift to autumn. The haze mirrored a collective state of mind, I felt, a wary tension marked by transitional discomfort. Halloween would come and go in five days’ time, less festive than usual, as holidays often are during presidential election season. I chatted with Duke about the abundance of enormous skeletons decorating so many lawns, stalking the hills and towering over hedges and pools. The uncanny giants, twelve feet tall, never failed to disarm. But it was the human-scaled versions, produced to telegraph realism, that we appreciated for their shocking lucidity. The popular mode was to toss one or two on the grass or over a fence post, and, in dedicating so little effort to stagecraft and presentation, an unexpected overstatement was made: entire neighborhoods became cluttered boneyards, as though dramatizing the day everything would end.

1

Image courtesy of the artist.

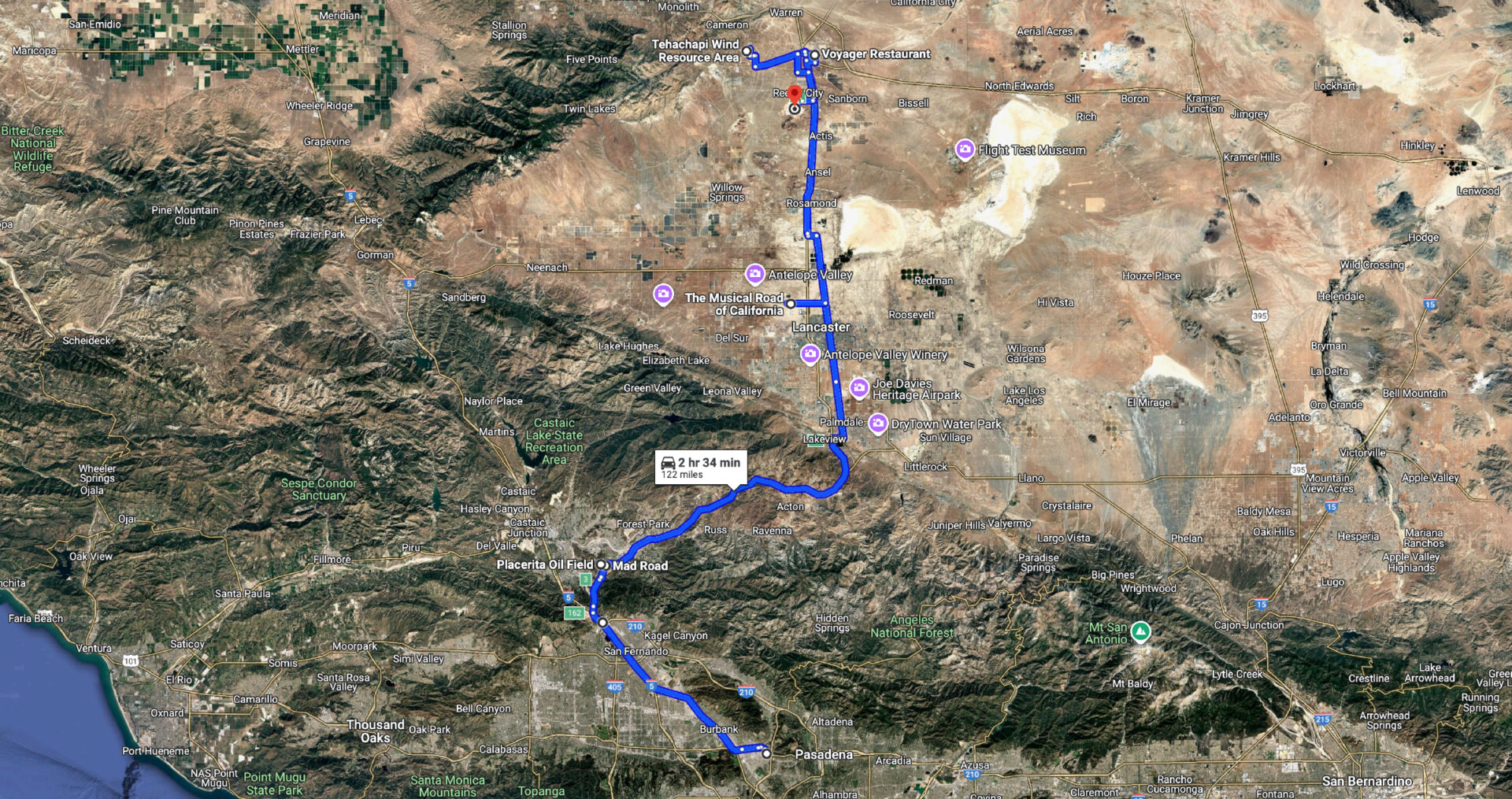

Traveling by road in Southern California never feels like visiting neighborhoods, towns, or regions; it’s more like passing through dimensions, zones, and substrata. We sailed by Beale’s Cut, a stagecoach trail at the southern line of Santa Clarita, and the sky turned blue as the gum in my mouth. Northbound, Duke had taken the Interstate 5 truck route, allowing a closer view of the Los Angeles Aqueduct Cascades before reentering the Antelope Valley Freeway and approaching the Placerita Oil Field, the first of our two destinations. (Later, we would drive to the wind farms at the edge of the Tehachapi Mountains). The Placerita Oil Field is a substratum of the Santa Clarita zone and belongs also to a category of land with boundaries that are not clearly visible, and have ambiguous regulations concerning public admittance. One field follows another there, compounding the ambiguity—Placerita gives way to the Newhall Potero Oil Field, and the Bouquet Canyon, Lyon Canyon, Aliso Canyon, Cascade, and Honor Rancho Oil Fields also crowd a four-and-a-half-mile radius shattered at its center by seismic faults.

Who controls what parts of Placerita, and what one finds there, are similarly convoluted. An entrance sign bears the insignia of SoCalGas, a large private utility company, and the Doty Bros. Construction Company. Another sign, farther on, announces Shadow Wolf Energy, LLC, a utility company I’ve never heard of. There isn’t a lot of information I can find; a petition submitted to the South Coast Air Quality Management District in December 2023 indicates that Shadow Wolf comprises, at least, a cogeneration station that provides electricity, steam, and other services to the field’s crude oil production facility. In general, the hodgepodge of signs, and lack of clarity about what belongs to whom, seemed to signal: “You don’t belong here, go away.”

Map data ©2024 Google.

But we decided not to go away, and instead accessed the field—just turned off the freeway and followed a service route named Mad Road to a clearing. There, a trio of pumpjacks preside over terraformed earth in almost every direction. The most immediate insults to the landscape are the 978 oil wells perforating the chaparral, of which 184 are active, 261 are idle, and 533 are abandoned, according to a 2018 groundwater quality report by the United States Geological Survey.1 The field has been tapped continuously since 1920, although gas, the report says, has not been extracted since 1990.2 The wells are identified as York 1, 2, 3, and 4, Winterer, Durham, Kraft, and Juanita—names that could easily be mistaken for racetrack dogs. It is this oddly tender, kenspeckle sensibility that I think, in part, attracts Duke to such forlorn places to ascertain in detail how humans use the world so casually and familiarly in the process of destroying it.

Duke’s previous visit to Placerita in the early 2020s, along with treks to the beleaguered Arctic, the burn scars of wildfires in Colorado and New Mexico, the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility in Colorado, the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center in Ohio, and the Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center, are all journeys that, one way or another, index ecological crisis and a civilization in decline. Much of his work is about bearing witness to these circumstances, cataloging the history of exploration, conservation, and wonder as regards the natural world, and marking the parallel history of human perception in relation to it. “Seeing seeing” is how he puts it, and, increasingly, the work is about seeing that seeing in ecological terms.

Image courtesy of the artist.

In 2022, Duke sailed north of the 78th parallel at Svalbard to make large-scale photographs of the land and seascapes with lenses from detached glacial ice, which he learned can be clearer than diamond. He “imagine[d] the glaciers of the world as giant lenses, naturally occurring optical elements polished by wind and snow.”3 Beset by trials worthy of an adventure novel, including a COVID-19 outbreak among the ship’s crew and extreme weather conditions, Duke nonetheless succeeded in more than demonstrating his proof of concept. The resulting photographs are, to his delight, legible, surprisingly romantic, and reminiscent of nineteenth-century pictorialism. He has come to think of them as the products of a glacial gaze, wearily drawing a bead on the follies of man.

The stout ice cylinders Duke used at Placerita were cousins of the glorious and tragic glacial-ice lenses. Cast from Southern California tap water (he had photographed the wildfire burn areas with lenses made from local tap water there, too), they extended the reach of his “glacial optics” concept beyond the Arctic Circle. Global warming is a global problem, after all. As it turns out, the glacier’s gaze peers with equal melancholy through frozen drinking water.

Using tools like those he developed for his Arctic photo shoot, Duke calibrated a Placerita lens according to the mechanics and optics of a single lens reflex digital camera. He extracted an ice cylinder from the unsealed plastic bag and inserted it into an elastic fabric sphincter at the center of a barrel he fit onto the camera’s body. Then, he pressed one end into the dimple of a custom-machined aluminum ingot, contact-melting the ice just enough to sculpt the curve of a precise focal length. Finally, flipping them around, he used the opposite, flat end of the ingot to smooth the back of the cylinder. A glass wafer between the lens barrel and the camera prevented moisture from compromising the apparatus.

Duke hardly had time to look through the camera’s viewfinder before a guard made it known we were being surveilled. Duke had been ejected by security officers on past shoots, and we readied ourselves for it to happen again, but the assertion that we had been seen seemed enough a declaration of territory to leave us otherwise alone. The act was a flex of power, as it were, by Placerita’s cryptic management. That the incident could be an allegory for the encounter between two disparate but tragically intertwined contexts—the glacial and the petrochemical—made the guard’s warning to avoid the machines, lest they burn us or poison us or soil our clothes, even more apt.4

Image courtesy of the artist.

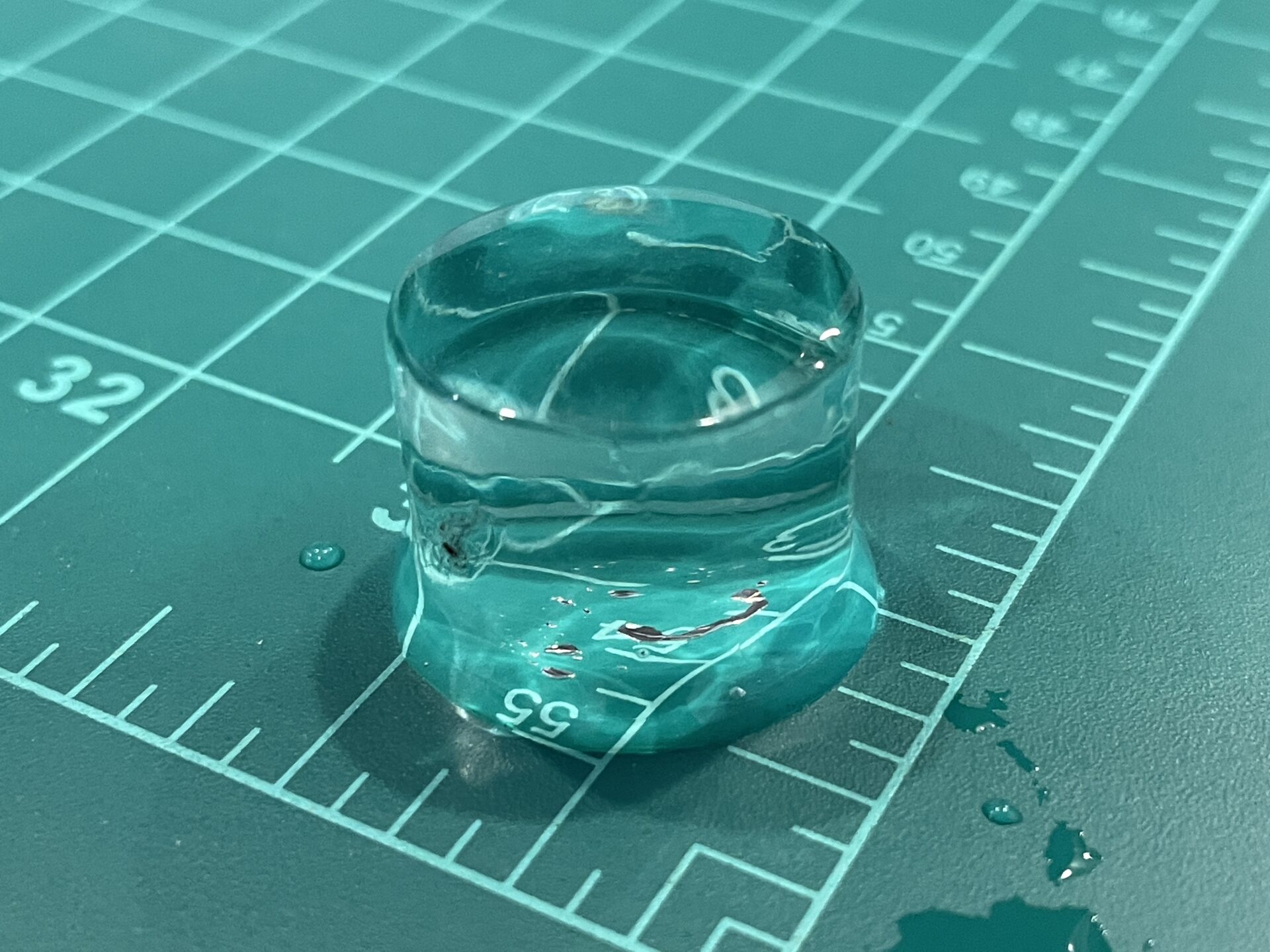

Dismissed, we moved into the field, stopping at intervals to admire our sanctioned proximity to the corroded, corrupting infrastructure. While photographing wildfire scars, Duke had discovered as an ice lens melts (it must be melting to work), “the focal length becomes shorter, resulting in a natural rack-focus effect” ideal for creating time-lapse sequences.5 He eventually set his tripod among the brambles to capture a montage of three wells on a mid-distant plateau. Interstate 5 sparkled in the background, feeding cars into the city. The camera’s shutter clicked and clicked and clicked. The minutes gathered. “This site reminds me of Griffith Observatory, perched up on the hills, looking into the mouth of Los Angeles,” Duke said. “It feels almost like a temple to oil.” The pumpjacks groaned. He dipped into soliloquy:

That mechanical sound is like hearing the metabolism of this infrastructure, which is our metabolism, the metabolism of the mass of humanity, the larger meta-organism of humanity. Oil is our metabolism, and that’s one of the scary things about the predicament that we’re in. It’s all fine and good to say, “Just stop oil today, let’s just get off it, kick it like a bad habit,” but the reality is that we’re far more embedded and invested in oil than we care to admit. We don’t have a viable alternative to be able to just pull the plug. In a weird way, recycling and electric cars have become more about privilege and money and being able to buy peace of mind, to be able to buy a “clean conscience” while the world burns.

People have asked me, “How can you reconcile the fact that you traveled to the Arctic? It’s a huge energy footprint to do that trip.” I don’t have an easy answer for where the line between personal responsibility and social engineering on a massive scale lies. I traveled to the Arctic not to vacation and enjoy the sights but to bring back a message. I went very much as an artist, aware of the responsibility of being the eyes for an audience back home.

It’s a complicated mess. And that’s part of what I wanted to explore in the oil field and the wind and solar infrastructure near Tehachapi. We have serious problems with the grid. Even if we built all the green energy capabilities that we needed today, we don’t have a grid to handle it. It’s a huge engineering challenge. It’s almost like building modern society up from square one. It’s almost on the level of “back to the drawing board.” If we’re lucky enough to get a second shot, our current society will probably be viewed as something like global civilization 1.0—our false start, when we got a glimpse of what global connectedness and a truly global society could look like before we realized that we built it on a completely false foundation and had to start again.

I could hear the camera cough discreetly as it made each exposure. It would be a study in surrender, I supposed. The resulting series of time-lapse photographs show a veil obscuring a lush yet industrialized environment. I asked Duke if his photographs are also about issuing a farewell to our current reality, and he continued:

I try to be nonpolemical about how I present the work and intentional about the viewing experience, which is not to say that I shy away from the research or the scientific message. The historical facts, as I have come to know them, are definitely a part of the work. But I’m also trying to create space for people to reckon with our reality. I think that’s a lot of what we’re struggling with, and I think we need to make space for acknowledging the challenges of that.

It’s understandable that people are really struggling existentially. It’s a pretty hard pill to swallow, to realize or to be asked to consider that there may not be room for infinite growth, for infinite expansion. It’s the downfall of the New Deal and the soaring Great Society—of this idea we could create a society that uses engineering on a massive scale to harness resources, centralize and increase efficiencies, and deliver prosperity to a widening group of people. Of course, I know that’s only one part of the story, and there were always problems with that vision, but I think there is a kind of disappointment we struggle with because our vision for the future has been ruptured. Utopia has slipped out of reach, and increasingly we see a different future of climate chaos and limited resources.

When Duke removed the barrel, it drooled tepid water, and the ice lens flew into the weeds, as if embarrassed to have melted. A raven swooped across the sky. Breeze stirred the vegetation. Placerita’s vibe was strangely calm. An ecosystem all its own was persisting in spite of the overground pipes and holding tanks and sucker rods. Its name derives from the Spanish placer, a term for alluvial sand, sediment that suggests the presence of gold—black gold, in this case. But in common parlance, it means “little pleasure.” A truck carrying rig workers hummed along a path, and I wondered if the work held little pleasures for them, or if such things were negligibly few and far between here.

2

The unincorporated community of Mojave lies twenty-six miles north of Lancaster, California, bounded on two sides by the Aerospace Highway segment of Interstate 14. A friend of mine once described the place as a pile of shards fallen from a thousand shattered mirrors, but I suspect the dead body he had seen informed his opinion. I’m not sure how Mojave’s residents would take such an account, though one would be hard pressed to argue all was fine. Its primary features are neglected houses and abandoned lots. I watched a man lazily smack a jelly palm with a machete. The life-affirming inspiration promoted by street signs bearing scripture seemed to have fled long ago. Except for the Mojave Air and Space Port, “the world’s premier civilian aerospace test center” and an economic oasis of cutting-edge aero- and astronautics just east of the cemetery on K Street, one could see the town going the way of nearby Reefer City, which was once a mining hub and now no place at all.6

The sunlight had thinned after we crossed over the mountains and into this new zone, the Lancaster-California City elbow, which cradles the Edwards Air Force Base and forms one half of the jagged Kern County trapezoid. Mojave was a gateway to our second destination, another aspect of its namesake desert: the Tehachapi Wind Resource Area (TWRA). Comprising eight-hundred square miles, five wind farms, and more than 4,700 turbines owned and operated by private companies, the TWRA is the largest wind resource area in California.

The Tehachapi turbines are so large and numerous they seem to pin the landscape to the horizon. And yet they are not the largest on the market. An article from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy reports that, in 2023, an average land-use utility turbine measured approximately 339 feet tall, with a rotor diameter (or, “the width of the circle swept by the rotating blades”) of approximately 438 feet, which is “about as tall as the Great Pyramid of Giza.”7 Had I come upon a turbine of this size, I suspect I would have fainted; as it happened, most, if not all, of the units in the TWRA either predate these scalar developments (the area’s infrastructural planning and development began in 1989) or adhere to requirements set by Edwards Air Force Base that limit their height to 400 feet above ground level so not to interfere with military procedures.8

Image courtesy of the artist.

(If you suspect I cannot describe the turbines with exactitude, you would be right. In general, renewable energy companies seem to practice a relatively higher degree of transparency about their existences and activities than their petroleum brethren, although making the specifications of their prime movers available to the likes of me does not appear to be a high priority. But I wanted to know whether I was looking at Mitsubishi turbine models MWT-275-28, MWT-250C, MWT-600G, or something else at the TWRA’s Mojave Wind Farm, and I don’t think it is too much to ask an “end-to-end” power producer like Terra-Gen to provide a little more information than “constructed through 1989/1999, this development spans X number of wind turbines across X acres.”9 That said, Terra-Gen is partially owned by Igneo Infrastructure Partners, “a global infrastructure manager and the direct infrastructure team of the First Sentier Investors Group,” which is a member of the global business firm and Japanese banking institution Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group, so I’m guessing I was not looking at something not Mitsubishi.)10

A dust storm carried on in another sector of the desert basin, but no dust rose outside Mojave; only the pure, coursing air blew. We entered the TWRA the way we had entered Placerita, conspicuously and not knowing what was allowed. The road draws vehicles through the middle of its field, and Duke pulled the car into a turnout midway. Thousands of rotor blades chopped the air. I followed Duke on foot toward a fence, a feeble boundary, to my surprise; I had been told security at wind farms was aggressive to protect the towers from being stripped of copper wiring.

A tower under 400 feet tall is still several hundred feet tall, and the turbines are monstrous, wondrous things. True, they are not without their issues, but until the pumpjacks can extract oil from our bones, turbines would seem the more responsible way to heat a home or boil some water. Freeze some water, too, so that we might see their potential through a steadier gaze.

Image courtesy of the artist.

Duke set up his tripod—a fresh ice lens hit by the ice press was already cinched into its fixture—and recorded the scene. The gigantic wind and the turbines’ keening discouraged us from talking, so in the spirit of Duke’s methodology—“The camera gets you to spend the requisite amount of time in a place—things open up when you slow down”11—I meditated on the scorched nacelle of a turbine that had immolated, and considered what he had told me en route to the Tehachapi:

In my work, I try to promote a more genuine and generous spirit around the action of meaning making, because an artwork is an interface with a perceiving mind. It takes a kind of courage to be creative because once you do something, there’s always the possibility of failure. But especially in these troubled times, it feels all the more important that we find ways to make that gesture. The opposite of creativity is complacency, or depression, or leaning into the downward spiral of destruction.

It takes a willful optimism to be creative in the face of such massive destruction, but I think it’s the only way out of this mess. If we fail, then it will be a failure of creativity and a failure of imagination. We need to invent a way of being in this world. We also need to remember. I don’t know what combination of past-forward looking this is, but people have known how to live in harmony with the landscape, with the ecosystem, within planetary boundaries.

It sounds perhaps naive to posit that creativity and poetry and art are our salvation, but I don’t really make distinctions between science and poetry and art. These are all stories we tell. They’re all human inventions and ways of understanding ourselves and describing our relationship to the planet.

Image courtesy of the artist.

The TWRA’s southern extension lists west to avoid Golden Queen Mining’s Soledad Mountain Project, an open-pit gold and silver mine in Soledad Mountain, which has been shaved away on the Tehachapi side. We passed it leaving Mojave, a mournful sight that invited Duke’s speculation:

I don’t think the world ending is necessarily a bad thing. It’s probably what needs to happen. This world needs to end. The question is, how much suffering and destruction and pain have to happen in the process? Are we able to transcend what is possible? As resources get tighter, there’s a real danger that bickering and fighting over the crumbs will accelerate that trend. What worries me much more than the practical challenges of the climate crisis are the worst parts of human nature—the social divisions that arise when you start putting stress on the system, which goes right to the seams. You’re going to see all the stress expressed as inequalities. That, I think, is the most daunting challenge.

A row of shiny electrical transmission towers marched crosswise through the wind farms, promising a new future built on renewable energy. But their scaffolds looked flimsy, not like the sprawling mine in its amputated mountain. No match, rather, for the Golden Queen on Silver Queen Road. She also operates twenty-four-hours a day.

3

Photograph courtesy the author.

Twenty-five minutes before the Voyager Cafe restaurant at the Mojave Wind and Space Port served me the worst veggie burger of my life, and forty-five minutes after departing the oil field, Duke and I made a small detour to an attraction on the outskirts of Lancaster known as the Musical Road. One of several around the world, the road features intermittent grooves that, when driven over, are meant to sound out the finale of Gioachino Rossini’s William Tell Overture. Due to a calculation mishap, about which the internet holds no shortage of commentary, the overture sounds like a jingle played by an untalented high school band.

That Lancaster’s Musical Road originated as a stunt for a Honda Civic car commercial and was approved by the city for its potential to attract tourists makes its existence all the more caustic. Its creators, who chose to harness design and engineering advances for a gimmick, should have at least had something to show for such a frivolous use of resources. The project’s failure speaks volumes—Sings! Rumbles! Reaps the whirlwind, as a Mojave street sign might say—about how truly misguided the priorities and applications of our finest practical knowledge are.

• • •

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Tristan Duke is a Los Angeles-based artist working in photography, holography, video, installation, and other experimental media. With a special interest in light, optics, and visual perception, Duke’s work explores how we seek knowledge about ourselves and the world. His work often incorporates technologies and processes of his own invention, such as his Glacial Optics project: using camera lenses made from ice to explore the glacier as a literal and poetic lens through which to understand our times. As the recipient of the 2023/2024 LACMA Art and Technology Lab Grant, Duke is continuing to build on his Glacial Optics Series, exploring cutting edge science on and in the glaciers with partners including the National Science Foundation’s Ice Core Facility (NSF-ICF), the Byrd Polar and Climate Research Center, the Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center (WIPAC), The Nevada Museum of Art Center for Art + Environment, and many others.

Duke has pioneered numerous holographic technologies, including creating the first ever 3D hologram vinyl records. He has created original hologram artwork for many albums and soundtrack releases ranging from Jack White to Guns ‘n Roses and Star Wars, earning him a Clio Award in 2016. His holographic album artwork has been featured on the Tonight Show, and in Rolling Stone, Forbes, The Verge, and Gizmodo. From 2010-2023 Duke worked in collaboration with artists Lauren Bon and Rich Nielsen, forming the Optics Division of the Metabolic Studio, a collective project seeking to recontextualize photography as a land-based medium and social practice.

He has shared his work internationally, with exhibitions and public talks at institutions including the MIT Media Lab, the Getty Museum, the Santa Fe Institute, Tamarind Institute, the de Young Museum, the Exploratorium, RISD, C|O Berlin, LACMA, MASS MoCA, and many others.

—

Title photograph: Artist Tristan Duke photographing a wind turbine at the Tehachapi Wind Resource Area outside of Mojave, California, 2024. Photograph courtesy of the author.

Documentation of ice lens equipment shows uncalibrated ice “blanks” and custom-machined aluminum ice press (left); a calibrated ice lens held in place by an elastic fabric sphincter (center); and a calibrated ice lens melting (right). All images courtesy Tristan Duke.

Grid formation: Tristan Duke, stills from Peak Oil 1, 2024. Digital video using a lens made from ice. Image courtesy of the artist.

- Jennifer S. Stanton et al., Groundwater Quality Near the Placerita Oil Field, California, 2018 (Reston, Virginia: U.S. Geological Survey, 2024), 6, accessed November 14, 2024, https://www.usgs.gov/publications/groundwater-quality-near-placerita-oil-field-california-2018. [↩]

- Ibid., 5. [↩]

- Wall text: Glacial Optics (Wreck of Hope) 2, Tristan Duke: Glacial Optics, SITE SANTA FE, Santa Fe, NM. [↩]

- Before taking his leave, the guard casually mentioned hydrogen sulfide gas and its “parts per million,” about which I would have appreciated knowing more. But the breeze was nice, and we had not been detained, so I settled for learning afterward that hydrogen sulfide occurs naturally in crude petroleum. In addition to “collect[ing] in low-lying and enclosed, poorly ventilated areas such as basements, manholes, sewer lines, underground telephone vaults, and manure pits,” it is “an irritant and a chemical asphyxiant with effects on both oxygen utilization and the central nervous system.” Moreover, it “can cause shock, convulsions, inability to breathe, extremely rapid unconsciousness, coma, and death” in high concentrations, and in the dispassionate words of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, these “effects can occur within a few breaths, and possibly a single breath.” Occupation Safety and Health Administration, OSHA FACT SHEET: Hydrogen Sulfide, accessed November 18, 2024, https://www.osha.gov/sites/default/files/publications/hydrogen_sulfide_fact.pdf. [↩]

- Wall text: Forest for the Trees, Tristan Duke: Glacial Optics, SITE SANTA FE, Santa Fe, NM. [↩]

- “About us,” Mojave Air and Space Port, accessed December 2, 2024, https://www.mojaveairport.com/about-mojave-air–space.html. [↩]

- “Wind Turbines: the Bigger, the Better,” Office of Efficiency and Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy, accessed December 2, 2024, https://www.energy.gov/eere/articles/wind-turbines-bigger-better. [↩]

- Pine Tree Wind Development Project Environmental Assessment: Final Environmental Impact Report (California: Los Angeles Department of Water and Power: Environmental Services and Bureau of Land Management, 2005), 2-100, accessed November 20, 2024, https://www.ladwp.com/sites/default/files/documents/Pine_Tree_Wind_Final_EIR_Enviro_Assess.pdf. [↩]

- “Mojave 16/17/18 Wind Farm,” Terra-Gen, accessed December 2, 2024, https://terra-gen.com/mojave-16-17-18. [↩]

- “Igneo Infrastructure Partners,” Igneo Infrastructure Partners, accessed December 2, 2024, igneoip.com. [↩]

- Tristan Duke, in conversation with the author, October 27, 2024. [↩]