Everywhere’s A Center: A Conversation With Channing Hansen

LOS ANGELES, 2024. On the occasion of the exhibition Energy Fields: Vibrations of the Pacific, featured artist Channing Hansen graciously invited Fulcrum Arts’ curator Patrick J. Reed to his Los Angeles studio, where they discussed Hansen’s ranging interests and labor-intensive practice. Working primarily with wool yarn that he prepares himself across many stages—including skirting, washing, dyeing, blending, and spinning—Hansen hand-knits vibrantly colored framed textiles according to algorithmic plans generated by a custom software program. These intricate plans echo the precision of DNA sequencing, and Hansen’s translation of them into textiles mixes traditional artistic methods and craftsmanship with scientific principles foundational to our understanding of the world.

PATRICK J. REED: Would you be willing to tell me about the first time, and maybe it was the only time, that you sheared a sheep?

CHANNING HANSEN: So, you know the pictures.

PJR: I’ve seen a photograph.

CH: Of me wrestling with a sheep…Well, I think that’s the key word here. I was helping out during shearing season in exchange for getting some of the fleece that would normally just be thrown out, plus I wanted to get in and learn the process. You have to grab the sheep by the back of its neck and lift up one of its hind legs. They’re used to it that way, and so they just give in when this happens. Then you can shear them. Not being so experienced, the first couple of times I did it, I didn’t get the leg right or it yanked out of my hand. I was like, I don’t want to hurt you, but the sheep was like, I’m not afraid of you! And the ground was muddy because sheep are sheared in the spring, when it’s still kind of wet. So, I’m holding the sheep and basically surfing over the mud. Zooming. Street skiing. Whoo-hoo! But eventually you do get hold of the thing. You get the leg right and you can just walk it over to the shearing station.

PJR: Where was that? And what’s the timeline here?

CH: That was in Temecula [California], I believe. Spring of 2011. You know, I’ve been knitting maybe fifteen years now, thanks to a friend of mine who was visiting from out of town and taught me how to knit. He has ADHD like me, and we were around the table talking, and he was knitting a hat. Usually, I have to be doing multiple things at once to pay attention, so if I’m on my phone, I’m listening to the conversation. It’s seen as very rude if someone’s on the phone because others think you’re not listening, but it actually helped me pay attention. This is before we really learned much about neurodiversity. But my friend with ADHD was sitting there talking and knitting and paying attention without needing other stimuli. He taught me how to do my first knit stitch. And then I started knitting for twelve hours a day.

I was “never not knitting” for at least a couple of years. Just obsessing. And I kept on going deeper and deeper and deeper. I think the more complex the area of knowledge, the more it can consume you. So knitting is one thing, and then you’re learning about making your own yarn, and then you’re learning about sheep shearing and sheep genetics. Some estimates say sheep have been bred to have white fleece for around five thousand years. They used to be all sorts of colors. The term “black sheep” means any sheep that has a spot of color, even though it might be an all-white animal. If there’s a tiny speck…it becomes lamb chops. One of the sheep geneticists I work with, Dee Heinrich, is trying to bring back the colors sheep had more than five thousand years ago.

PJR: What is the most surprising color?

CH: Dee Heinrich found a color called Paddington Blue.

PJR: How did this research change your relationship to the final product, the final artwork?

CH: I used the first fleece I got to learn how to spin. So, there was that kind of relationship. But I think just having an intimate relationship with one’s materials helps you understand how and what the materials want to do. There are people who, for instance, spin yarn, but they get the fleece prepackaged and pre-colored. Doing it that way, you don’t understand as much.

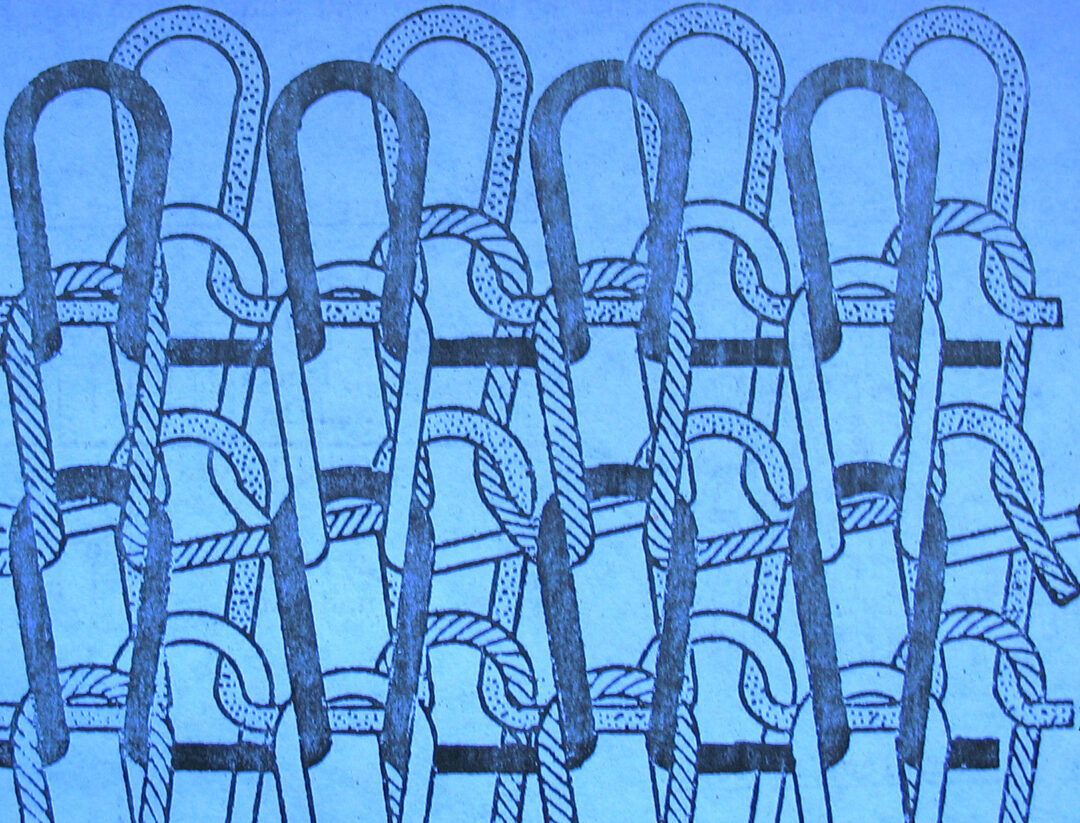

For example, there’s a thing called twist. All yarn is spun in a circle. And there is twist that goes clockwise and twist that goes counter-clockwise. When you go to a yarn store, you’re likely going to get one type of yarn, the Z-twist yarn. But when I make it myself, I make a ball of Z-twist and a ball of S-twist. They each pull in a different direction. If I knit them together, they pull on each other and they create this tension that you almost don’t notice. It’s almost imperceptible. But that tension becomes inherent to the work. I combine different types of natural and synthetic fibers during spinning, and there’s a feedback loop created when you work with raw materials—they start to tell you what they want to do.

PJR: It takes you deeper and deeper.

CH: Feedback loops show up in my work, for example, when the algorithm I’m using says to do something with the yarn in a place that would undermine the actual structural viability of the artwork because it doesn’t know what a square is or what a plane is or it’s just randomly saying, Do this here. So, I might have to struggle or wrestle with what the algorithm is telling me to do versus what the work can bear.

PJR: I want to know more about this algorithm because I don’t totally understand how you use it.

CH: The algorithm was invented by Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī around 800 CE. An algorithm is a set of instructions. My earliest algorithms were written in [the programming language] Python and my digital algorithms are still written in Python, though I sometimes use analog algorithms as well. They’re basically lists of variables, of different stitches and colors and patterns and ways of going. I even have a list of mistakes to choose from. I press the spacebar on the keyboard and the algorithm randomly picks from an array of these things, then says, You’re doing this now.

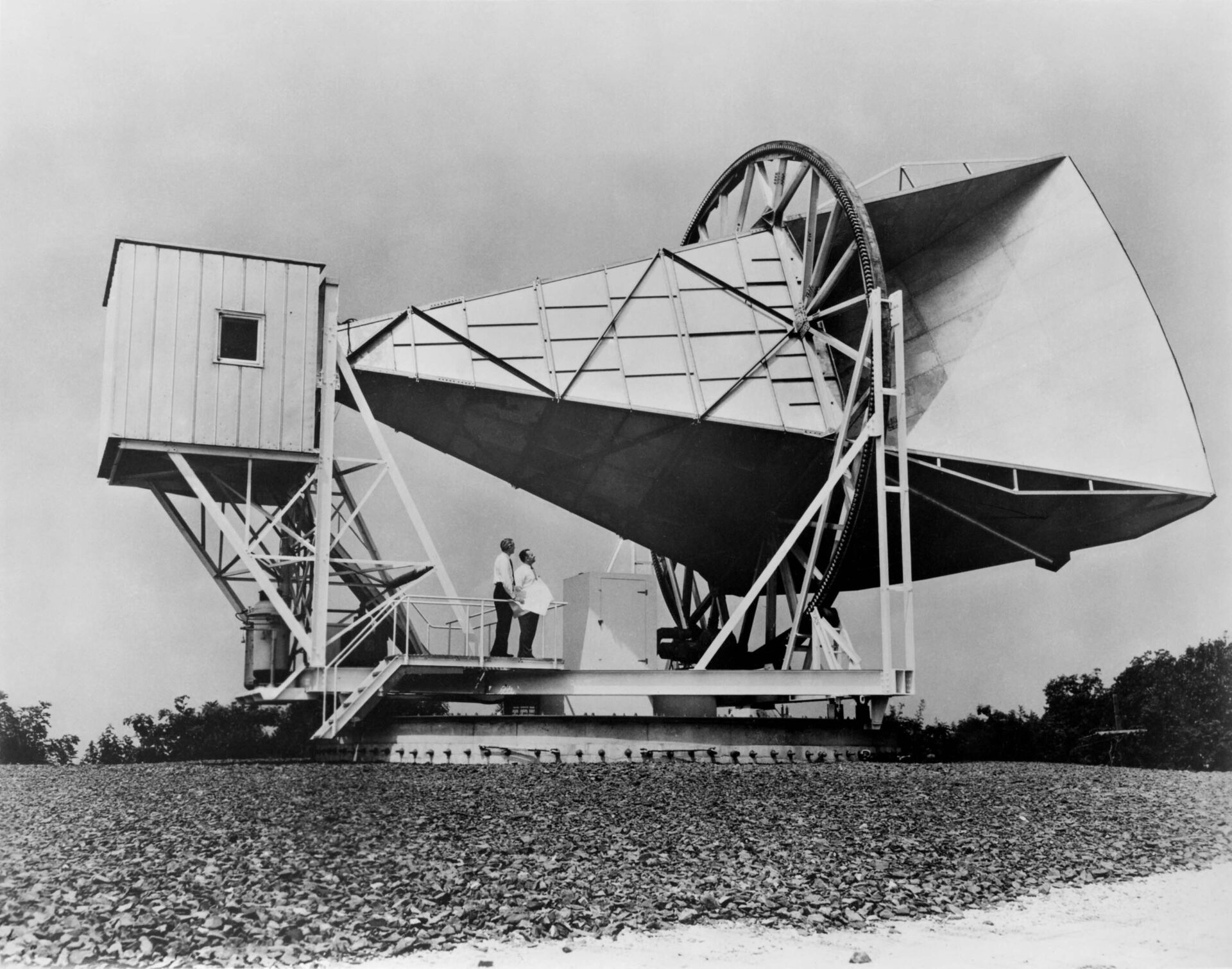

Computers can’t be truly random—only pseudorandom. But I really wanted to get randomness. With my first Quantum Paintings, I wanted to take my subjectivity out of the work because I was struggling with the problem of subject matter, which is really fraught. And I had been, for years, fascinated with quantum physics and all the different interpretations.

PJR: How do you determine the variables?

CH: They’re almost like the DNA of the works. From one body of work to the next, they kind of mutate. I try to introduce new elements to distinguish the bodies of work somewhat. So, in that sense, they’re different, but related genetically. As I move on, some elements are left out, some are added in. Over the years, I’ve developed my own vocabulary of these patterns or stitches. Some of them are loosely based on actual stitches you would find in any stitch dictionary.

Oftentimes, the stitches I use are almost unrecognizable at the scale I work in. It’s like you have this microscope, and you’re kind of zooming in. Then there are areas where you can see the knitting has actually been done on a much smaller scale. So, it creates another tension in the work. In some places, everything around it is pulled in, like there’s a black hole. It’s like the density or the mass of it is pulling all the stuff in.

PJR: Do atavistic elements from previous projects ever reappear?

CH: Sometimes, yes. For a show in 2021 in New York at Susan Inglett Gallery, I hired a friend of mine who was an AI programmer. He created an AI construct that was trained on all my work to date, all the shows I had ever done. And we asked it, What does a Channing Hansen look like? It spit out 10,000 patterns of which I then knitted around twelve. I called the show I, Algorithm. The works themselves, I thought, were pretty amazing. My L.A. gallerist, who has shown me the longest, could recognize different elements from different shows in one piece.

PJR: Did you have that experience, too?

CH: Oh, yeah. When I was knitting them. Of course.

PJR: When you remove the subjectivity from the work, does that affect your relationship to the final piece?

CH: I have no real idea what it’s going to look like in the end. And I don’t know how long it’s going to take to finish. No clue. And not all of them make it out of the studio. Sometimes, after weeks and weeks, I get to the end, and I’m ready to frame it, and I think, This…does not work. And then I carefully unravel it and try to reclaim as much of that yarn as possible. Other times, I’ll be two-thirds of the way through and think, Oh my God, this is going to be amazing.

Sometimes I get to a part in the algorithm’s instructions that says, Do “x” for the next twenty rows. I then have to visualize how twenty rows of that are going to look and work structurally and compositionally with the other elements. If I want to keep going to the point of framing the piece, I may have to compensate for those twenty rows somehow, or it’s not going to stretch properly. I’m trying to balance these elements.

PJR: It’s kind of like reading music.

CH: Yeah, you have to picture the music in your head.

PJR: How was Cosmic Fourier Fabric [2023], your piece in Energy Fields, made?1 Were any unusual or distinct applications required?

CH: That one was particularly challenging because I was using Fourier transform data of cosmic microwave background radiation, and it did a lot of weird stuff. I also used a variable that changed the sizes of the stitching, which caused the work to have these very open spaces alongside very tight spaces.

I’m fascinated with the Fourier transform and how ubiquitous it is. And very few people even know what it is. If you listen to an MP3 or open a jpeg, you’re using the Fourier transform algorithm. I read a good explanation of it that used the example of a milkshake. You’re drinking a milkshake, and you say, I want to know how they made this, so you break it down into milk, apple juice, yogurt, and berries. The process is a way of figuring out how something is made, breaking it down into its constituent parts. With an MP3, it breaks down the data and makes it much smaller. It compresses it. When you open the file, the program reconstitutes it. But it’s also a lossy technology. If you open and close a jpeg a million times, it slowly degrades. There are these tests where an Instagram post, for instance, or any kind of Facebook post with a jpeg in it, is shared by ten million people. That opening and closing so many times and reproducing and copying slowly degrades the picture. As the file loses data, it becomes almost a blur. It’s like xeroxing a Xerox.

PJR: That makes me think of entropy.

CH: People sometimes think that entropy is the general tendency of things to fall apart, when really, it’s all about energy change. Energy never dissipates, it just changes. Because of the second law of thermodynamics, it creates different patterns of energy. In the very short span of a person’s lifetime, they will experience “falling apart”—physically, mentally, et cetera. But when you expand the frame to much larger periods of space and time, it doesn’t look so much like things falling apart, since there’s a finite amount of ways molecules fit together. That limits the number of possible outcomes, but when you look at an infinite amount of spacetime, things are most likely coming together rather than falling apart.

PJR: Tell me about the Thomas Guide [series of street atlases].

CH: Before MapQuest and Google maps, the Thomas Guide was how you navigated the streets of L.A. Every car had one. Angelenos over a certain age see one and say, Oh, look, A Thomas Guide. I remember those from my youth! The older versions list hotels, hospitals, museums, chambers of commerce, cemeteries, colleges, with their phone numbers in the back. Like [opens a vintage edition Thomas Guide and flips to a page] the Bay City Business College in Inglewood. Its phone number was Oregon 4-4-100 before area codes were introduced.

What I like about the Thomas Guide is the idea of taking a topological surface like Los Angeles and then charting it onto these navigable maps over many, many pages. And each one of these pages is its own topological surface. I just love it as system of charting maps, kind of like a Choose Your Own Adventure. A lot of my work revolves around manifolds and surfaces. You know the old topological joke about how a doughnut and a coffee cup are the same?

PJR: Can’t say that I do.

CH: To a topologist, a doughnut and a coffee cup are the same, just different mappings because they both have a surface that has a hole in it. It’s called a torus, aka a doughnut. Technically, humans are also doughnuts, a surface that has a hole through the center.

PJR: In your artist book Mapping the Universe Popular Atlas: 2024 Edition [2024], which accompanies Cosmic Fourier Fabric and contains the data used to create it, you riffed on both these topological concepts and the format of the Thomas Guide. But instead of charting a region of Southern California, it charts a portion of the universe, per the title. If I wanted, could I use Mapping the Universe Popular Atlas for navigational purposes?

CH: If you were a three-dimensional shadow of a four-dimensional being trying to navigate the universe, you could theoretically use it, but the cosmic microwave background data exists everywhere in space and time. I chose a map without our galaxy because there’s no center in the universe. Or, more exactly, every place is the center of the universe.

Photograph by Christopher Wormald. Courtesy Fulcrum Arts.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Channing Hansen is a polymath who draws inspiration from the inherent beauty he finds in biological processes, genetic patterns, chaos theory, fractals, and the Fibonacci sequence.

Recent institutional group exhibitions include those at Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (2024); Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles (2022); Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation at California State University, Los Angeles (2022); Long Beach Museum of Art, Long Beach, California (2019); Casas Riegner, Bogotá (2018); Wexner Center for the Arts, Columbus, Ohio (2018) and Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, New York (2017). Hansen’s work was included in Made in LA, curated by Ann Philbin, at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2014).

Select solo exhibitions include: I, Algorithm, Susan Inglett Gallery, New York (2021); Channing Hansen, Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Beverley Hills, California (2019); Pattern Recognition, Simon Lee Gallery, Central, Hong Kong (2019); Morphogenesis, Stephen Friedman Gallery, London (2018); and Fluid Dynamics, Marc Selwyn Fine Art, Beverly Hills.

Hansen’s work is held in the collections of Art Institute of Chicago; Dallas Museum of Art; Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; MOCA, Los Angeles; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Stedelijk Museum; and The Ahmanson Foundation, Los Angeles.

—

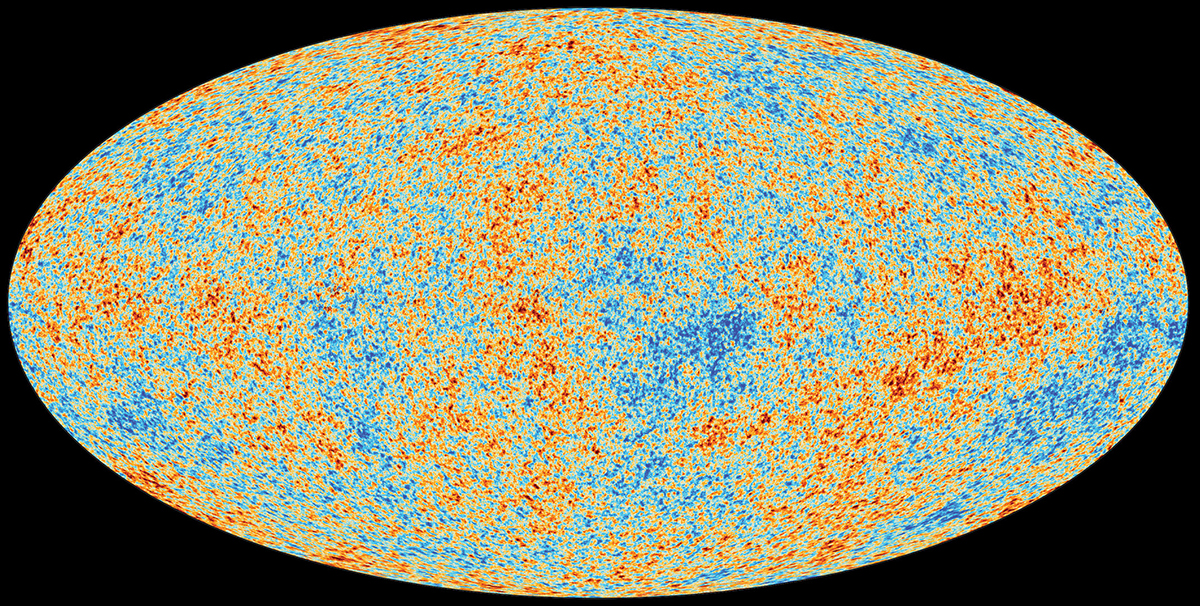

Title image: Planck’s view of the cosmic microwave background. It is a snapshot of the oldest light in our cosmos, imprinted on the sky when the universe was just 380,000 years old. It shows tiny temperature fluctuations that correspond to regions of slightly different densities, representing the seeds of all future structure: the stars and galaxies of today. Image © ESA/Planck Collaboration.

- Cosmic Fourier Fabric gives form to the artist’s research on cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR), understood as the afterglow of the big bang, or the residual heat of creation. To determine the work’s composition, Hansen used NASA’s 3-D modeling data of CMBR from the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe, the Planck probe, and the Fourier transform equation to seed an algorithm. Knitted into a pattern that corresponds to the algorithm, Cosmic Fourier Fabric models an infinite-dimensional topology: space-time as a literal fabric, or the big bang as canvas. [↩]