Immediate Perception: A Conversation With Mo H. Zareei

LOS ANGELES x WELLINGTON, New Zealand, 2024. On the occasion of the exhibition Energy Fields: Vibrations of the Pacific, featured artist and musician Mo H. Zareei joined Fulcrum Arts’ Patrick J. Reed in a video call where they discussed Zareei’s childhood in Tehran, his formative creative influences, and his fascination with what he called “audio-visually confrontational works” that have the power to elicit raw emotion. Zareei’s “sound-based brutalism” aims to produce such an effect, and draws from the developing history of light, sound, and kinetic sculpture as well as brutalist architecture and minimalism. When speaking with Reed, Zareei makes the case that the phenomenological qualities of matter are an essential consideration for the production of any memorable sensory experience.

PATRICK J. REED: When you talk about your influences, you cite Japanese artist Ryoji Ikeda, postdigital minimalism, and Ekbatan Town in western Tehran, the last of which seems to have had the most profound and lasting effect on you. I’m interested in knowing more about Ekbatan and your experience growing up there.

MO H. ZAREEI: Ekbatan was part of Tehran’s development plan under the Shah of Iran to appeal to the middle class or create a middle class through land reforms and urban development. Ekbatan was initiated before the [1979] Iranian Revolution, but I don’t think it was fully realized until after the revolution. When I was born, it would have been just a few years old—less than a decade, for sure. So, it was a residential megastructure that was quite different from the more organic or traditional urban structures and textures around it at the time. It was a really ambitious project. It’s still probably the biggest—or one of the biggest—housing complexes of its kind. I know housing projects are often associated with urban decline, especially in the US or even the UK, but this was a different story. The idea here was to bring a lot of people from small satellite cities or towns together to build an urban population and middle class. It was a new entity, essentially.

And you could feel, even as a kid, that everything was new. The trees were small, the shops were empty. You had to walk to the surrounding neighborhoods to get yogurt and bread and stuff like that. As I grew up, so did the complex. It’s been, for a number of decades now, a self-sufficient neighborhood. It has its own schools, its own shops, a couple of hospitals, and a big population. Getting out of Ekbatan and then coming back to it always felt so unique. The giant buildings that are always the same, standing there. The uniform, Lego-like puzzle around you. The big blocks of concrete. As a kid, you feel embraced by a sense of security, a sense of status…in a good way.

Tehran’s a big city. Back then, it wasn’t as big, but it was still busy—not the quietest urban environment. But when you walked or drove into Ekbatan, all of a sudden you could hear things differently because the concrete buffered a lot of the urban noise. The buildings made these isolated zones, where city noise was immediately replaced with the sound of the trees, for example. That seems poetic, but it was actually like that. If you walked down to the C2 Block next to the big highway, the sound of the cars was always there. That was the “car zone.” Or A1, where I grew up, was next to the airport. Plane engine sounds were always there. These acoustics were unique because you didn’t have a lot of ordinary street noise, but you always had hyper-focused soundscapes from the airplanes or the big highway in the distance that would bleed through the concrete.

The buildings had their own unique features. The fan coils, for example, you wouldn’t find in most typical houses or apartments in Iran. They were uniform and they were, I think, contracted just for Ekbatan. They had their own sonic feature that they added to the houses in summertime. There was always this vrrrrrrrrrrr sound going in the background in every apartment.

PJR: Were you always captivated by brutalism, or did your interest in it develop over time?

MHZ: I had no idea what brutalism was. I just knew that I loved my apartment block, and I loved my neighborhood. It wasn’t until I started my PhD that I started thinking about this obsessive, geometric ordering of raw material and my interest in minimal, grid-based, audio-visually confrontational works.

For a PhD, you need to be able to articulate why what you do is important. You can’t just say, Hey, this is cool. You have to think more deeply. Why did I like the things that I liked and want to make work with these specific aesthetics? I was home visiting my family, walking amongst those same buildings, and I looked around and thought, Well, there you go. The brutalist sensibility, its aesthetic, had been ingrained in me just from growing up there and finding solace in the architecture. It’s slightly romantic, but a lot of people who grew up in Ekbatan have that sense of attachment and belonging. It’s not just me. I have a lot of friends who share a sense of deep nostalgia for it, especially the ones who have left the neighborhood or left the country.

Oh, but brutalism. What is that? That sounds a bit aggressive. Brutalism as a movement has nothing to do with the English word brutal. It comes from béton brut.1 The premise behind it was a celebration of unadorned, conventionally anti-beautiful material. It was architecture through sculptural form; a carefully considered arrangement of raw materials. It related to the postwar widening of socialist movements to provide public goods—affordable housing, affordable schools, affordable libraries. And concrete was cheap and affordable. So, it became the quintessential material for brutalism.

But a lot of people don’t like it. I remember other family members visiting and someone would say, That’s not architecture. That’s just a block of concrete. A lot of negative connotations became associated with brutalism a long time after its inception. Dark, rough buildings with sociopolitical baggage from Hollywood contexts that show the Eastern Bloc behind a gloomy filter. What is the term? Concrete monstrosity. But it’s like the types of sounds I want to make. They’re raw and unconventional. You wouldn’t play them for your grandma. But that’s not music! There was a parallel there, in terms of the conventional attitudes toward buildings and sounds and the philosophy behind the arrangement and presentation of the materials.

Also, I thought there was the need, at least in our niche academic circles, for a way to address brutalism as a frame of reference. Brutalist ideas had started to come back after the postmodern years. There was a yearning for the ideals of the postwar era, to bring back the functionality of modernism, when a house was supposed to be, you know, functional, built for people. So, I thought that it was appropriate to use brutalism as a frame of reference. And I defined my attitude toward sound-based artworks through it.

PJR: What developed out of this realization?

MHZ: To be able to point out and represent the beauty of these things, in a sense. To create or provide some visceral expression in the form of a digital piece of music or an audio-visual installation—and to be able to see and hear the thing that is being presented at the same time and in a sensory way, that’s the big thing. If you think about visuals and architecture, that relationship creates a visceral reaction, too. You stand in front of a brutalist building, and you probably either hate it or you love it, immediately. You don’t start analyzing it, you know? The first impression, to me, is important in the work. Something should immediately convey a big part of its essence. That’s something the digital track or visual installation can do.

PJR: Why is that important to you?

MHZ: Because that’s how I enjoy the work of others. When I go to a gig or when I’m at a gallery or when I put my headphones on or turn some music on, that first impression is everything to me. I want to be captivated and in the work. If I can make enough time or space in my head to analyze the work and be distracted by different things, the work isn’t quite successful as I’m experiencing it. I want that piece of art to just hit me in a physical, visceral, sensory way. Then, later, I can think about it, what it is, how it’s made, all that stuff. But if that first visceral connection isn’t made, I get distracted.

You know when you see a beautiful view? Or a sunset? Or the moonlight? You’re just taken by it immediately, right? That moment of hypnosis. For a second, you kind of don’t think about it, you just absorb the audio-visual information that is your surroundings. I like that. It’s not a direct link, of course, to brutalist architecture, but there’s something there, too, that creates raw emotions in you. And I want to somehow re-create that in my work.

PJR: The experience is an experience of immediacy.

MHZ: Immediacy is a very good word. There’s a sense of unease and confrontation when something’s almost too loud, but not quite. Something’s almost too quiet, but not silent. Something’s almost too bright, but tolerable. Almost too symmetrical…just easing around the edges of sensory perception. That’s an area where you can focus to create a sense of immediacy and tension.

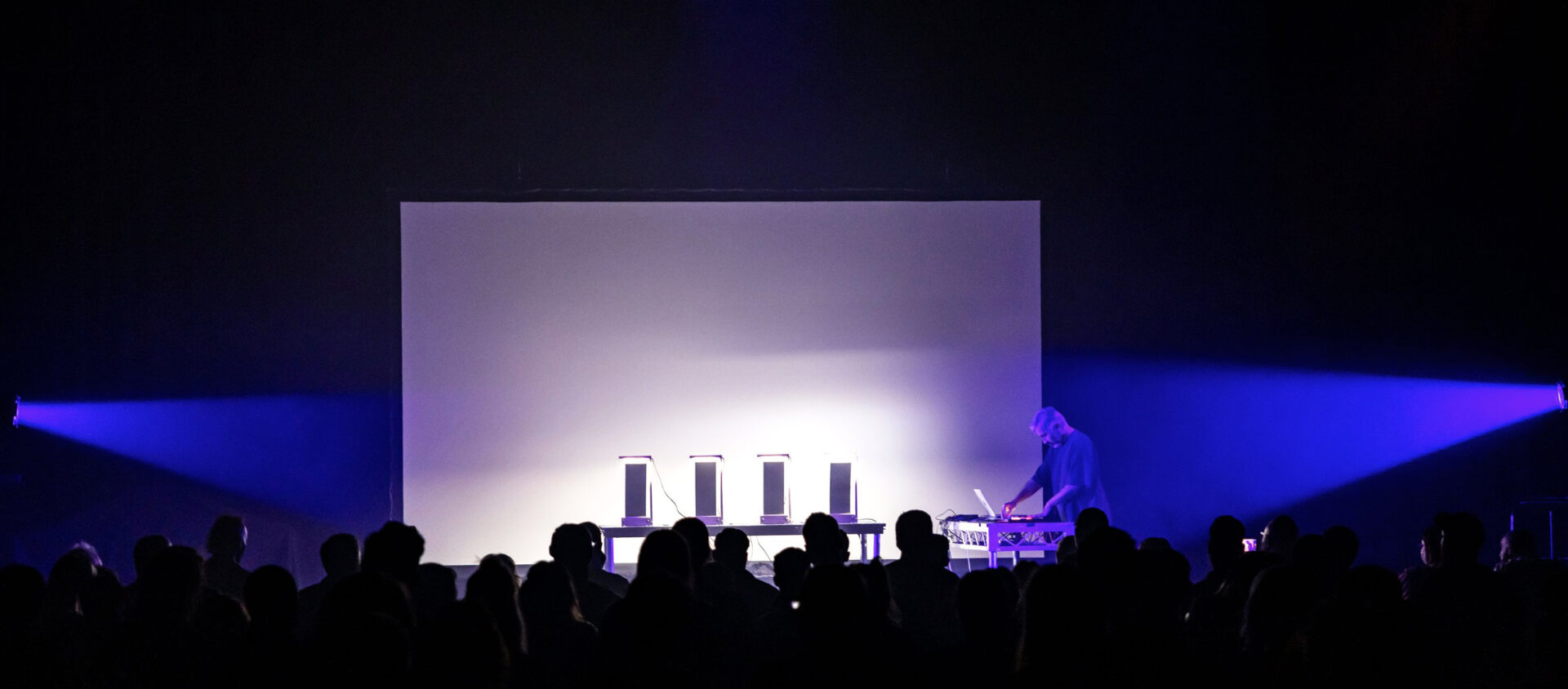

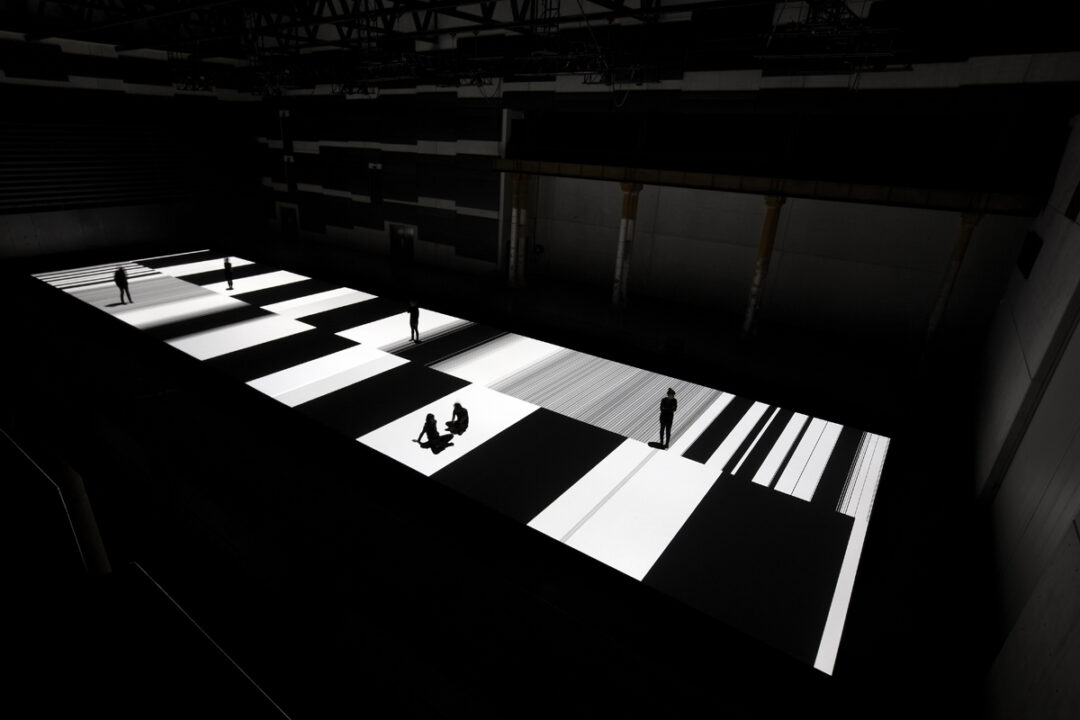

test pattern [n° 5] is exemplary of Ikeda’s immersive projects.

PJR: Tell me more about the influence of minimalism on your work.

MHZ: I remember I was in New York staying with some friends, and one of them said, Hey, there’s a really cool exhibition. You might like it. We went to the Park Avenue Armory, and the show was Ryoji Ikeda’s the transfinite [2011], one of the most captivating pieces by him, in my view. An onslaught of raw, basic audio-visual information, giant barcodes, black-and-white strobing. In that big warehouse it was really, actually immersive. You felt like a piece of information. And this huge work was made using basic click sounds and sinewaves. I immediately knew I liked it, and it was similar to the music I listened to, like the early glitch and IDM [intelligent dance music] and experimental electronic music made after the 2000s. Postdigital minimalism, so-called, I think, to differentiate it from the art movement of the 60s and 70s.

This was also around the time I was starting my second degree, when I had moved to the US to study at CalArts [California Institute of the Arts in Valencia, California]. There, I learned more about the old-school minimalism, and I saw that there was definitely a link between the two waves, though they were realized completely differently, in different historical and cultural contexts. Later, when I was reflecting and thinking about my PhD, I saw parallels between both minimalism and brutalism. If you talk to an architectural critic, they might get mad at me, but it’s the same set of moves: using raw material, using basic and geometric shapes, taking away ornamentation, taking away distractions. One was for the functionality of architecture, one was for presenting everyday objects as art. So again, there were links that I thought could be related to the broader framework of sound-based brutalism.

PJR: What about your first degree in physics? I imagine those studies are still relevant to your practice.

MHZ: Now that’s an interesting one. Without going on a tangent about how the public universities in Iran work, I’ll just say it’s a bit of a roll of the dice what you end up with. You go through a university entrance exam, and everybody gets to rank their favorite subjects to study at their favorite universities. Priority is given according to what you’ve scored on that exam, so things start filling in. When I was eighteen, I wasn’t passionate about physics or anything like that. In high school, I was okay at math and physics, and that’s a typical thing—you do something you think you might be good at. But the first half of my education was pure suffering. I wanted to play the guitar. I wanted to make music. Instead, I had to learn about quantum physics, and that wasn’t cool. But I needed to finish the degree. I knew if I wanted to completely sidetrack to music, at least I had to show my family that it wasn’t because physics was hard that I let it go. My engagement with my physics education—and this is one of the points that I regret a lot—wasn’t very deep. I studied hard to pass the courses, and I did okay. I got my degree.

I wasn’t formally trained as a musician, so when I was going to move overseas to do something with music, I felt inadequate. I tried to look for something that would see my physics education as not a complete disadvantage. Then I came across the Music Technology Program [at CalArts], and I thought that maybe they’d accept me. Little did I know they thought that my physics degree was really amazing. And I remember that they were all impressed [laughter]. When I started studying at CalArts with professors who were teaching me how to write code or use a breadboard to wire things up to make an interesting sound from scratch, that was a different context for my studies. My four or five years in physics classrooms had given me a foundation to makes sense of waveforms, to understand the concept of frequency, to understand a diode, to know how to write a piece of code with a variable that changes. So that understanding was there, and it helped me make up for my lack of formal musical training.

At the same time, being introduced to artists like Ryoji Ikeda and that school of minimalism made me realize the actual physics of the work are quite interesting from an artistic point of view, like waveforms and the way they interact with each other. These physics principles, which I had studied and didn’t care for much, suddenly became interesting, and part of that is, of course, the idea behind Material Music [2018].2 It’s not a scientific piece of music. But it does take inspiration from that stuff, for sure. In a lot of work that I’ve developed, the physical phenomena in everyday life, light and sound and all of that, is reduced to its core. I use that as a source for artistic exploration. In a sense, there’s a minimalist attitude towards these phenomena.

PJR: How far can the concept of brutalist sound sculpture be applied to your sound and audio-visual objects?

MHZ: Because it is an academic exercise, to a degree, to come up with some term as an umbrella framework, it’s hard to calibrate. What is the true brutalist piece of sound art? It becomes a little bit jargony. But I guess what’s missing from the work I’ve been able to do with the experience, expertise, budget, and facilities I’ve had available to me is scale. Of course, when we talk about brutalist architecture, there’s always scale, although I haven’t introduced sound as brutalism in a one-to-one direct transcoding of the architectural to the sonic. Scale is important in making immediacy impactful. Scale and quantity. That’s why being able to be fully immersed in Ryoji Ikeda’s work, or the work of an artist like Zimoun, is important. When you’re surrounded by these objects, and when they’re scaled to embrace you, that sense of a visceral connection is made much easier. To bring a bit of scale to the temporal monolith, which I’ve been using as a metaphor for the sonic aspect of those brutalist principles, that’s where I can see it go.

PJR: Are you moving toward a radical or irreducible honesty in your work?

MHZ: Quite the opposite, in fact. I was for a long time, but some of it was potentially influenced by my academic experience, where you are conditioned to justify every single decision and have solid reasoning and be a purist when it comes to concept realization. But over the past couple of years, I’ve become a little easier on myself, bringing elements to the work that might be cheating if it comes to a purist realization of an abstract idea. These elements help create the visceral experience of the piece and think about dramaturgy not just in a theoretical, abstract, conceptual way, but also in a way that can make the work more impactful. I like to have a little bit of, I would say, flexibility when it comes to realizing those concepts—which might mean bending the concept a little bit behind the back, without necessarily disclosing that’s what is happening—or compromising the pure conceptual stuff for a more immediate or effective reception from the audience’s perspective.

That was definitely something I experimented with in the Brutalist Noise Ensemble V2 [2023], which I premiered at the Ωhm Festival in Brisbane last year. The piece does use solenoids and big metal sheets to create sound. But then I have a whole set of recordings of the same material, of the same sheets, that are digitally processed to make the experience of the work feel more powerful. With the first Brutalist Noise Ensemble, everything was acoustic; there was no amplification. But with the second version, I added a synthesizer. My goal is to keep the cohesion between sound and image so that you don’t question the piece as a whole. You don’t think, What is that? That’s not the sound of the motor. You think, That’s the sound of the motor, even though I’ve added a synth in the back. You have the immediacy, like foley in film, you know what I mean? Not every sound comes from the action. It’s done after the fact, but it feels right.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Mo H. Zareei is an electronic musician, sound artist, and researcher. Using custom-built software and hardware, his artistic practice covers a wide range from electronic compositions to kinetic sound-sculptures and audio-visual installations. Regardless of the medium, Zareei’s work aims to highlight the beauty in the basics of sound and light production, and reductionist audio-visual elements that draw inspiration from physical and architectural principles.

He has exhibited his work at international events and festivals including Ωhm Festival (Brisbane), the International Symposium on Electronic Art (Brisbane, Montreal, Vancouver, and Dubai), the New Interfaces for Musical Expression conference (London), the Modern Body festival (The Hague), the International Community for Auditory Display conference (New York), the International Computer Music Conference (Perth), SET X CTM festival (Tehran), and New Zealand Festival (Wellington).

Zareei is a featured artist on Streaming Museum and his work has been published on CreativeApplications.Net, Vice, and Fast Company. His project Rasping Music [2014] was the recipient of the first prize for sound art at the Sonic Arts Award 2015, and his installation Material Sequencer[2020-2021] was shortlisted for the Aesthetica Art Prize in 2024.

Publishing his electronic music projects under the moniker mHz, Zareei’s albums have been released on Room40 (Australia), LINE (U.S.), Important Records (U.S), leerraum (Switzerland), and KASUGA Records (Germany).

He holds a BS in physics from Shahid Beheshti University of Tehran; a BFA in music technology from the California Institute of the Arts; and a PhD in sonic arts from Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, where he is a senior lecturer in composition and sonic arts, and creative director at aotearoa audio arts.

—

Title photograph and videos courtesy of the artist.

- In French, béton brut means “raw concrete.” [↩]

- Material Music (2019–20) is a kinetic sound sculpture that exploits the materiality of sound production to highlight the effect of physical material in the transmission of vibrational energy experienced as sound. The sculpture comprises eight pairs of actuators, each programmed to strike various solid blocks of matter, including wood, glass, marble, and copper. Upon activation, the actuators strike the blocks simultaneously, but they slowly fall out of sync; the left and right actuation instances of each unit become offset by minuscule delays driven by variations in the speed of sound as it travels through each material. Material Music is on view as part of Energy Fields: Vibrations of the Pacific from September 15, 2024 to January 19, 2025. [↩]