SURFACE AND MEMORY: A CONVERSATION WITH KATHIE FOLEY-MEYER

LOS ANGELES, 2024. Following the exhibition Descent and Transformation, Vol. 1: Voyages to the Americas at Residency Art Gallery in Inglewood, California, Patrick J. Reed spoke with the exhibition’s curator, Kathie Foley-Meyer, to discuss her own practice as an artist and scholar.1 Her ongoing project Descent and Transformation—a collaboration with the filmmaker Max Marcellus—is a vehicle for organizing and sharing her research on the territoriality and temporality of Blackness. In this work, she looks to the ocean as a nexus of timescales and a location for an evolving definition of the human. What comes to the surface in her writing, videos, sculptures, and paintings are renewed concepts of interconnectedness, memory, visibility, and transparency.

PATRICK J. REED: Your practice supports many streams of research that, I would argue, belong to a larger project concerning ideas of access—access to the past, access to stories lost or stolen, access to potentialities yet unrealized—while remaining discrete in their own terms. It’s a complex network, and I’m curious how it all began.

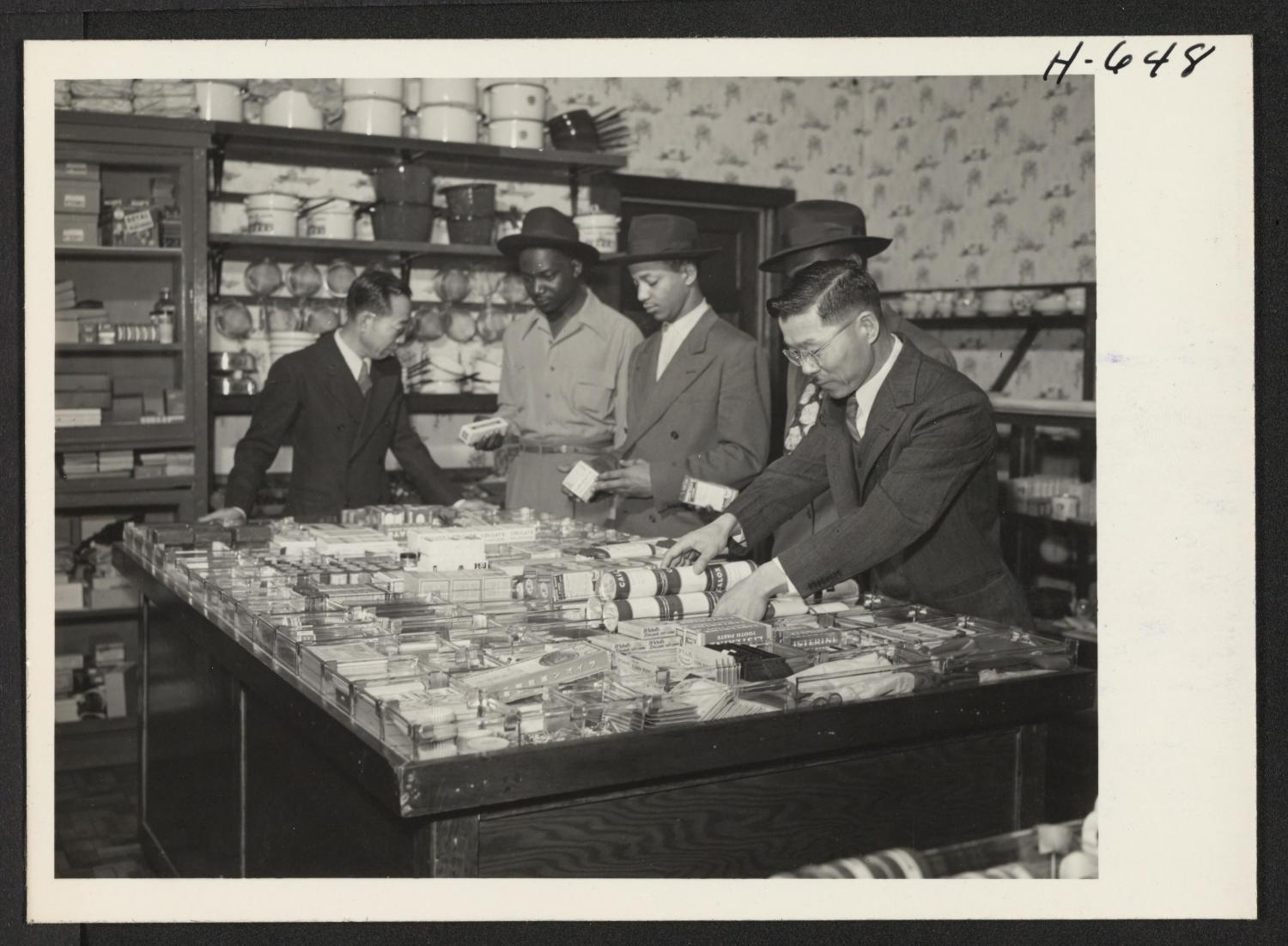

KATHIE FOLEY-MEYER: There was a period in Los Angeles during World War II when African Americans, many of whom worked for the war industry, moved to Little Tokyo after Japanese Americans were interned. The neighborhood became known as Bronzeville, and a lot of jazz clubs opened up. Because the war industry was going twenty-four hours a day, many people worked the late shift. They would get off work and go to Bronzeville to listen to Charlie Parker or Miles Davis or others play jazz at Shepp’s Playhouse or the Finale Club. I became fascinated by this period, but when I walked around the streets of Little Tokyo, I couldn’t see any evidence of that history—there wasn’t a trace.

So, I started doing research, which spanned over the course of several years, in Little Tokyo and greater L.A. I visited the Visual Communications Archives in Little Tokyo, and there’s a newspaper archive in South L.A. at the A. C. Bilbrew Library, where the Black Resource Center is. I found old editions of Black newspapers and the Los Angeles Times. At the Central Library, I looked at the Los Angeles Sentinel and The California Eagle, too. I was really intrigued and thought, “I want to bring this period, which was obviously very vibrant, to life. How can I do that?”

Around the same time, I was taking a course at the Museum of Neon Art, and I realized that glass was a perfect way to work with these ideas of transparency and seeing through layers. I made multiple casts of my hands from bronze-colored glass. Together, the casts spelled out “Bronzeville” in American Sign Language. I also etched the names of businesses and people who were alive during the period onto three glass panels [for a display background], and at the top I etched Japanese characters that roughly translate to “Blue Copper Town,” which was the phrase I got when I put “Bronzeville” into a translation module. This became one of my first sculptures, Bronzeville [2010].

I love the way glass can make things visible but also invisible, and it seemed a perfect way to talk about a history that was hidden but gradually, or suddenly, coming to light. But I knew I wasn’t going to use glass forever. I had other things I wanted to say, and I had to figure out the materials I wanted to use to say them.

PJR: What about your interest in signs?

KFM: My sign obsession came from photography. I took a photography class at Santa Monica College years ago, before I ever started making art, and I largely photographed downtown L.A. because that’s where I was working. I’ve always been fascinated by signage, so a lot of the things I photographed were signs. Because we live in a multilingual city, there are some signs that have meanings that are not intentional. There used to be a store on West 8th Street close to South Rampart Boulevard. It was a ninety-nine-cents store catering to Latinos, and its sign said, “Latinos $0.99.” And I would always read that and think, “It sounds like they have people for sale in there”—but you knew what they meant. The store was in the middle of a neighborhood on the edge of Koreatown, and it was interesting for me because there were also signs in the background in Korean. I always used to say—and I still say—that L.A. is like an architectural dig, but all the layers are above ground. You just have to walk around and look for them.

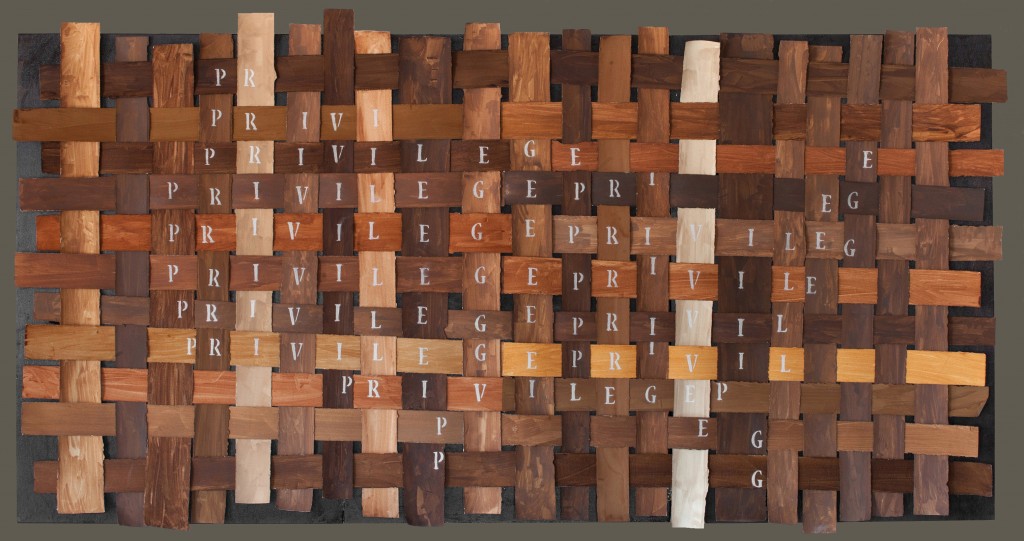

I’m really fascinated by things marked by a presence or an absence. Not being there is still a way of being there. I’m always interested in what is being said and not being said as the subtext of a statement. Who has the privilege of being legible, or who has the privilege to speak? Who has the privilege of being understood? Who has the privilege of just existing visibly in a space? I’m always thinking about that. It’s always a subtle part of how I’m working.

PJR: The alphanumerical stencils you use in your paintings, with their links to signage and forms coming apart, seem to have a direct connection here.

KFM: I like the definitive nature of text, but when you stare at letters or numbers long enough, they stop carrying the meanings ascribed to them, and they just become shapes. I used to make my own stencils. I would print a letter and carve it out and double up the paper. I would put clear nail polish on the sides to make a hard edge I could draw around. They were sort of precise, but they also weren’t. I liked the roughness of them. But then I felt they needed to be more precise, so I would order them, or I would have somebody else manufacture them. But sometimes, when I need that roughness, I make them myself.

PJR: When does that occur? When do you feel like you need the roughness?

KFM: When I’m dealing with certain aspects of residence time or the decomposition of a body, which is something I did a lot of reading about while I was writing my dissertation [at the University of California, Irvine]. For the past several years, I’ve been focused on the concept of ocean memory—the memory of my ancestors who did not survive their voyages through the Atlantic and the Pacific and are now in what’s called residence time. Residence time is the scientific term for the time it takes the ocean to completely consume something. Our bodies are composed largely of water and salt. Sodium has a residence time presence in the ocean of up to 260 million years. So, I’ve been fascinated with the idea that my ancestors, in a sense, will outlive me. They left hundreds of years before I was even born, and they maintain a presence in the ocean, a kind of aliveness, if you will, that will outlive me after I’m gone.

If a body goes into the water, depending on where it goes, it might be subject to aggressive animals that are attacking it—sharks and whatnot—but eventually it drifts, making its way to the bottom, and it encounters all kinds of sea life, both visible and microbial. It becomes food for all these different processes in the sea. And I feel like that type of disintegration—entering those life cycle processes—is sometimes expressed better with letter shapes that are not precise. Then there are times when the opposite is true. It really depends on how I’m thinking about it.

Most recently, I’ve wanted the letters to be clear and legible, but even the manufactured stencils start to fade over time. There’s always a disintegration process in the residence time work, but it’s constantly evolving. I like the idea of something that is constantly evolving and changing all the time because it also ties into themes of Blackness and fugitivity. Adaptability, or the ability not to be captured—not just in the sense of not being enslaved, but not to be captured or defined by culture—is a recurring theme in Black studies. And in the case of Black people, we’re frequently defined against something. So, the fugitive, in visual terms, can become really interesting to play with.

PJR: How did the coupling of residence time and ocean memory develop?

KFM: I first saw the term “residence time” in print was when I was pursuing my PhD. I read Christina Sharpe’s In the Wake: On Blackness and Being [2016], where she talks about residence time and the 260 million years, and from there I thought about ocean memory because the entire book is about memory. So, I searched for “ocean and memory” online, and the Ocean Memory Project came up. I reached out to them and didn’t hear anything back until I discovered that one of the professors was at UC Irvine.

After tracking him down, he invited me to present at the first Ocean Memory Project conference, on genomics and cognition. Each presenter gave a two-minute presentation designed around a question, and my question was, “Where are they?” Where are my ancestors who did not survive their voyages? And will we eventually develop a technology that allows me to access them, access their residence time presence? There is DNA testing in the ocean. Obviously, it’s not at the phase yet where you can do that, but what if it was?

The Ocean Memory Project was funded from 2016 to 2023, but there are projects that are offshoots, and one of them is the Ocean Memory Performance Project, which I’m involved with. It’s been very interesting, and it’s inspired a lot of work for me. After the cognition and genomics conference, there was a round of funding you could apply for, so Max Marcellus, who is another Ocean Memory Project member, suggested we collaborate. This collaboration became the project Descent and Transformation.

We received funds to do underwater photography, but we realized that there was probably going to be more than one version of the project, and I thought the version we were working on with our art would be first. But as it turns out, UC Irvine approached me about curating a show on the Black Pacific, and I thought, “Well, that dovetails.” So that’s why the exhibition, Descent and Transformation: Voyage to the Americas [2024], is the first part.

PJR: Tell me about Twelve Voyages [2017], an earlier painting of yours, which is directly related.

KFM: I have a set of CD-ROM disks that were part of the original publication that became the SlaveVoyages website. David Eltis, the Robert W. Woodruff Professor Emeritus of History at Emory University, had all this data about the slave trade from insurance records and other records he compiled onto a set of CDs. I was fascinated by that, so I ordered them. Then I did nothing with them! In fact, I don’t even know where they are.

Later, Emory University made the data available online, so I spent a lot of time diving in and out of their database. You can look up records in all kinds of ways. You can look up voyages by date. You can look up voyages by state. I was really interested in voyages that came out of the East Coast, because it’s not necessarily a territory that we associate with slavery, even though it was very involved with the slave trade. In fact, I am currently an artist-in-residence for Slavery North, an initiative at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, investigating the slave trade in Canada and the northern United States. We tend to focus more on the South because our popular culture pushes us in that direction—there’s hardly any person I know of who hasn’t seen Gone with the Wind [1939] at least once. So, I picked voyages that had originated mostly in Rhode Island and New York, but I was struggling with what to do with all this data. “How do I make it come alive?” The result was Twelve Voyages, but I felt like I’d really just cracked the surface, which is why I’m still working with that data.

PJR: The piece is exemplary of your work in that it’s visually striking yet deals with a painful topic. The stenciled numbers, for example, which appear to float over an abstract color field, are statistics about the human cargo transported and lost during the Middle Passage. What’s your take on that interplay? Do viewers often respond immediately to the painting’s visuality before knowing the full story behind it?

KFM: They do. But if you think something is beautiful, you think it’s beautiful. It doesn’t mean it doesn’t also contain pain. It’s the beauty that draws you to it. So that’s a good thing. If you’re having a reaction, then the reaction you had is exactly the reaction I would like.

There’s an argument to be made: “Oh, you’re dressing up something painful.” I don’t look at it that way. I don’t think exposing a human being to unending images of trauma has the same effect as introducing them to trauma through something that is pleasurable to look at and makes them think. To borrow a phrase from Anthony Trollope, “the way we live now,” we are constantly exposed to images on our phones. We’re overwhelmed with images constantly. Breaking through all that is even more of a challenge for artists. And the more you expose someone to something, whether it be pain or pleasure, they’re not going to react the same way over time. I think our brains can only respond to so many images of trauma before we become conditioned to it. Having seen those images doesn’t necessarily mean that we are more connected to each other as human beings. What I’d like my art to do is to have those human connections, and if you can come to them through beauty, then I’m happy to have you do that. I don’t think it takes away from the message of it.

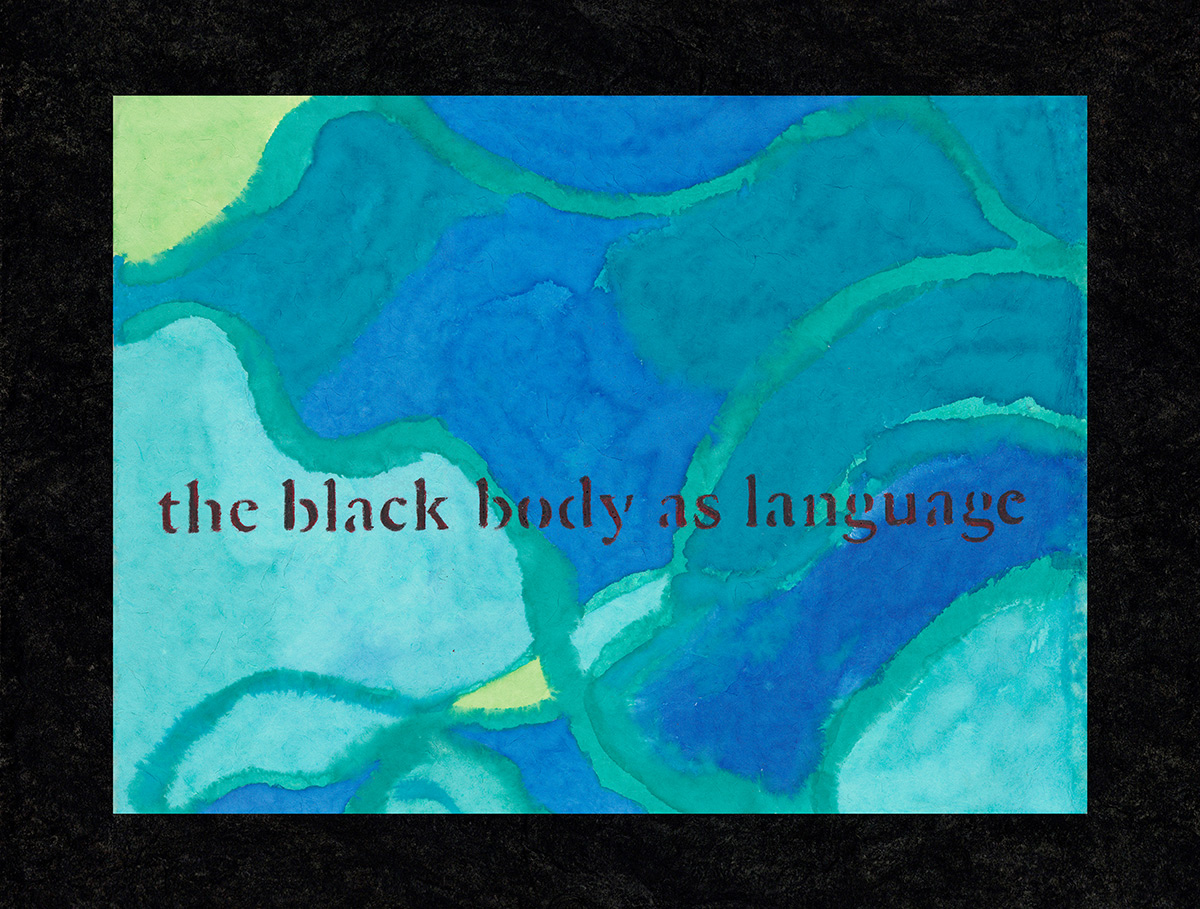

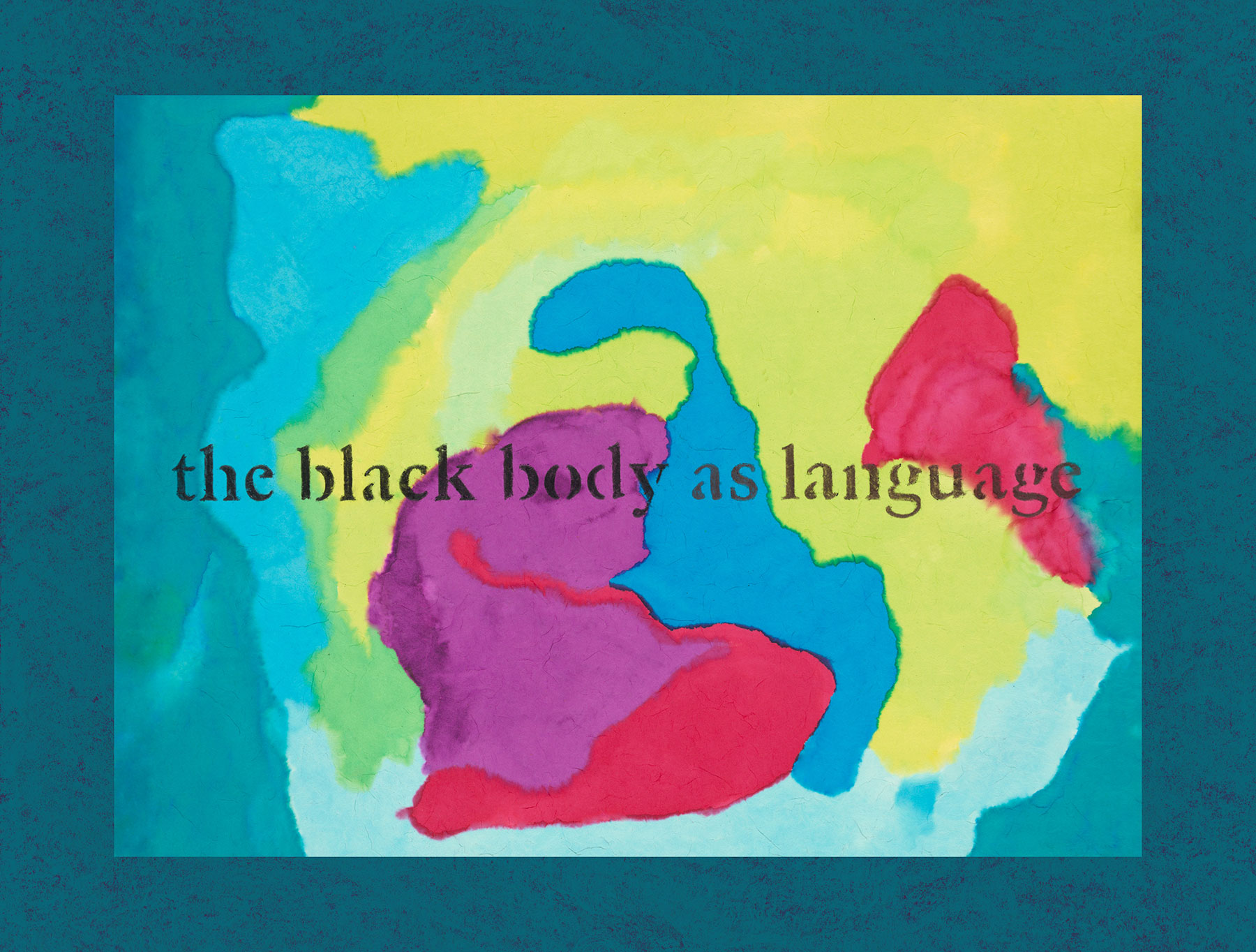

PJR: At the 2022 Fulcrum Festival Deep Ocean/Deep Space, you gave a presentation titled, “Descent & Transformation: The Art and Science of Ocean Memory,” which introduced the audience to your concept of the “Black body as language,” which you defined as an interactive and generative mode of communication with other forms of life. “It is not a spoken or written language,” you said, “but one form of life encountering another and the process by which both are changed.” Could you elaborate on this?

KFM: When I say, “mode of communication with other forms of life,” I mean that process by which the Black body is consumed and excreted by microorganisms or other forms of sea life—that’s the communicative process I’m referring to. It’s a generative process. In that context, you’re nutrients for another form of life. You could look at it also as consumption as a form of communication. I’m assuming “communication” because you can’t really consume something unless you know it actually exists.

I’m also thinking about the fact that, as human beings, we come from the ocean, and there are millions and millions and millions of Black bodies in residence time in the ocean. So, let’s just say, for the sake of argument, we get wiped out by an asteroid, and life as we know it on this planet ceases to exist but the planet doesn’t die. We’re just not here. These millions and millions of Black bodies could be part of the next iteration of the human. That language, that articulation of the human, could regenerate. That’s what I’m referring to, which is exciting to me, even though I’m not going to be around to see it.

There’s the human cycle of regeneration, which some people think is under threat simply because so many people are not having children, but I don’t think we’re going to run out of humans anytime soon. I do think we have to take steps to not run out of the planet that we live on. We have to preserve it in a way that makes it sustainable for all of us, not just some of us.

PJR: If the ocean has a memory, does it also have what one might call a “gaze”?

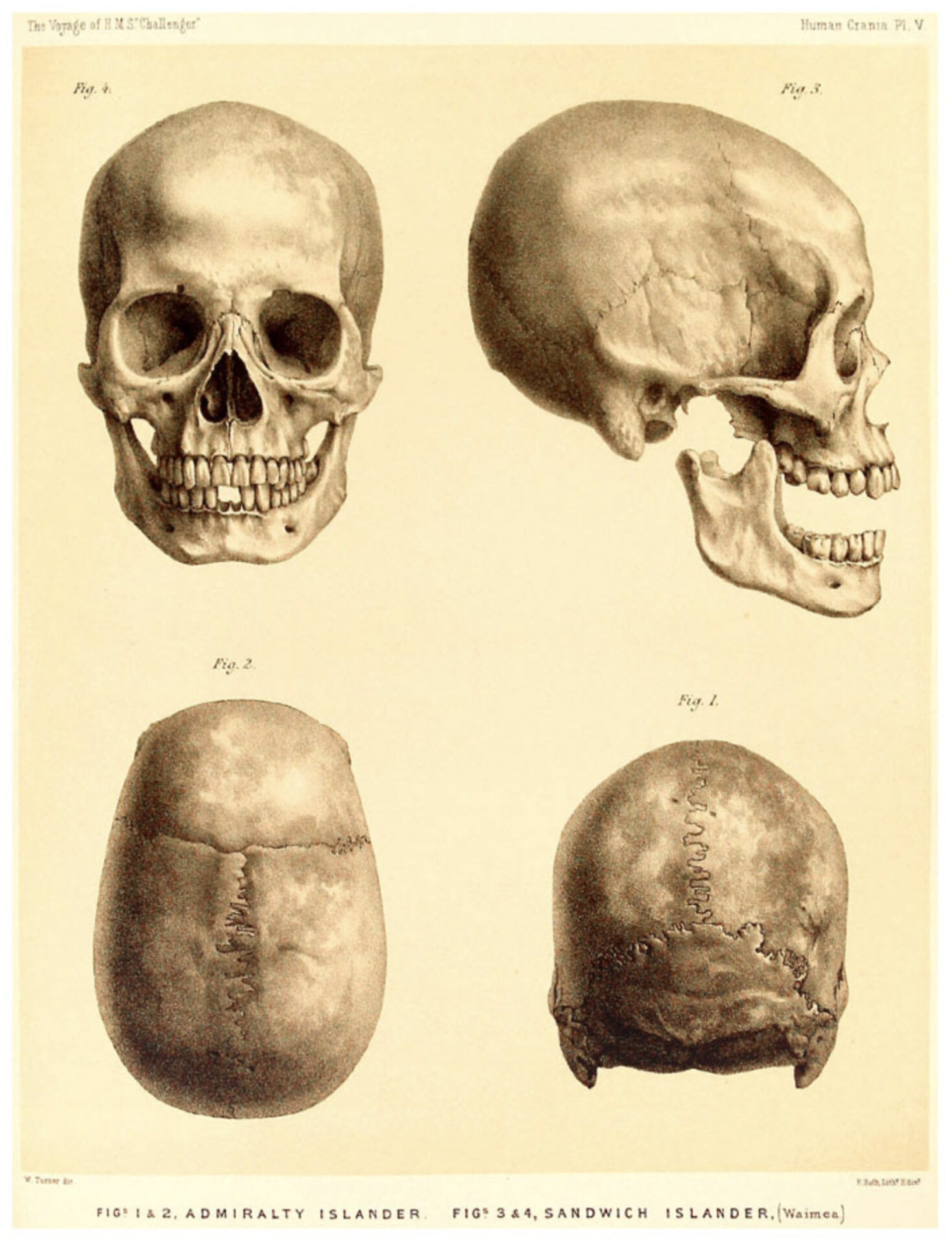

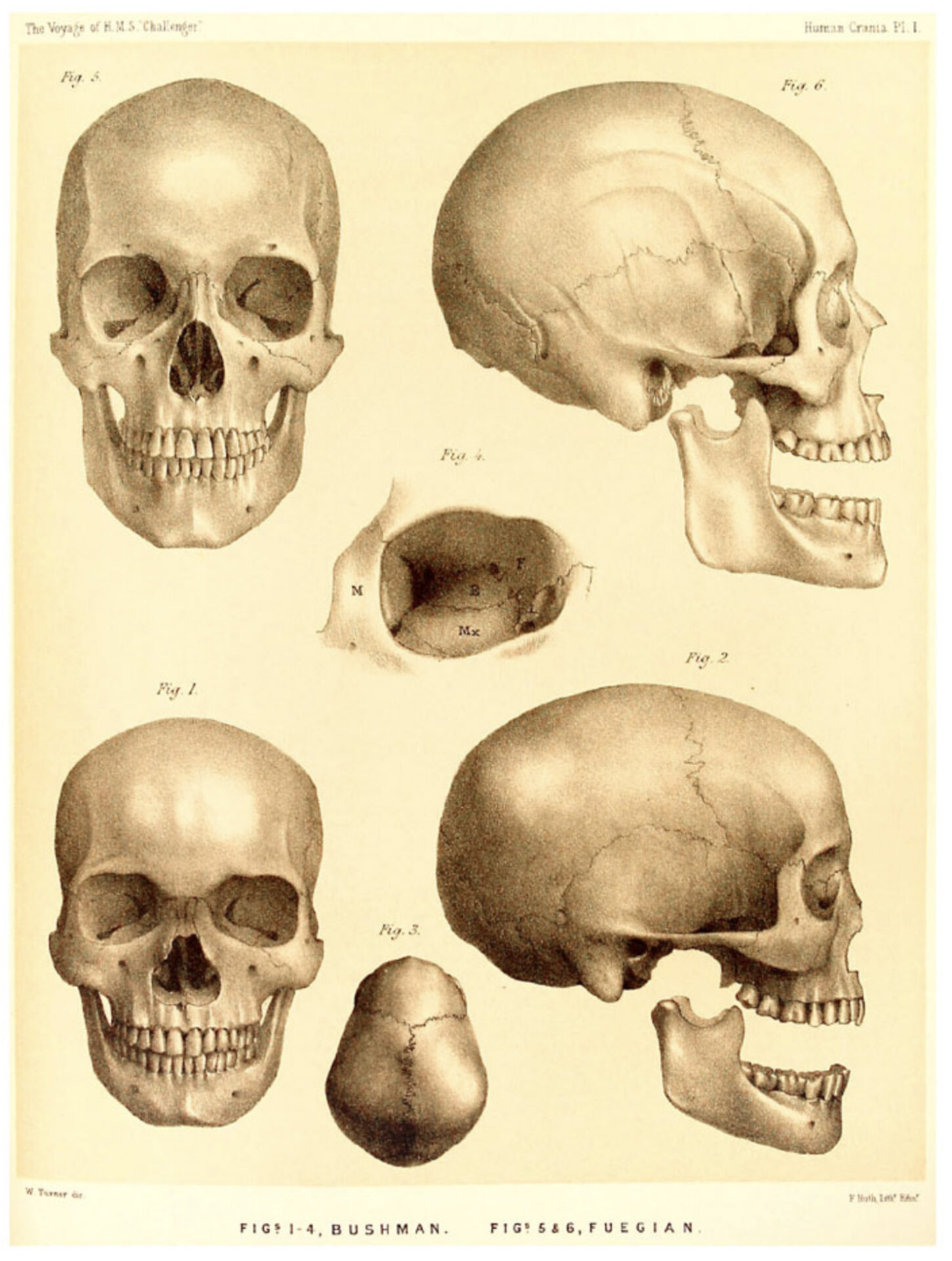

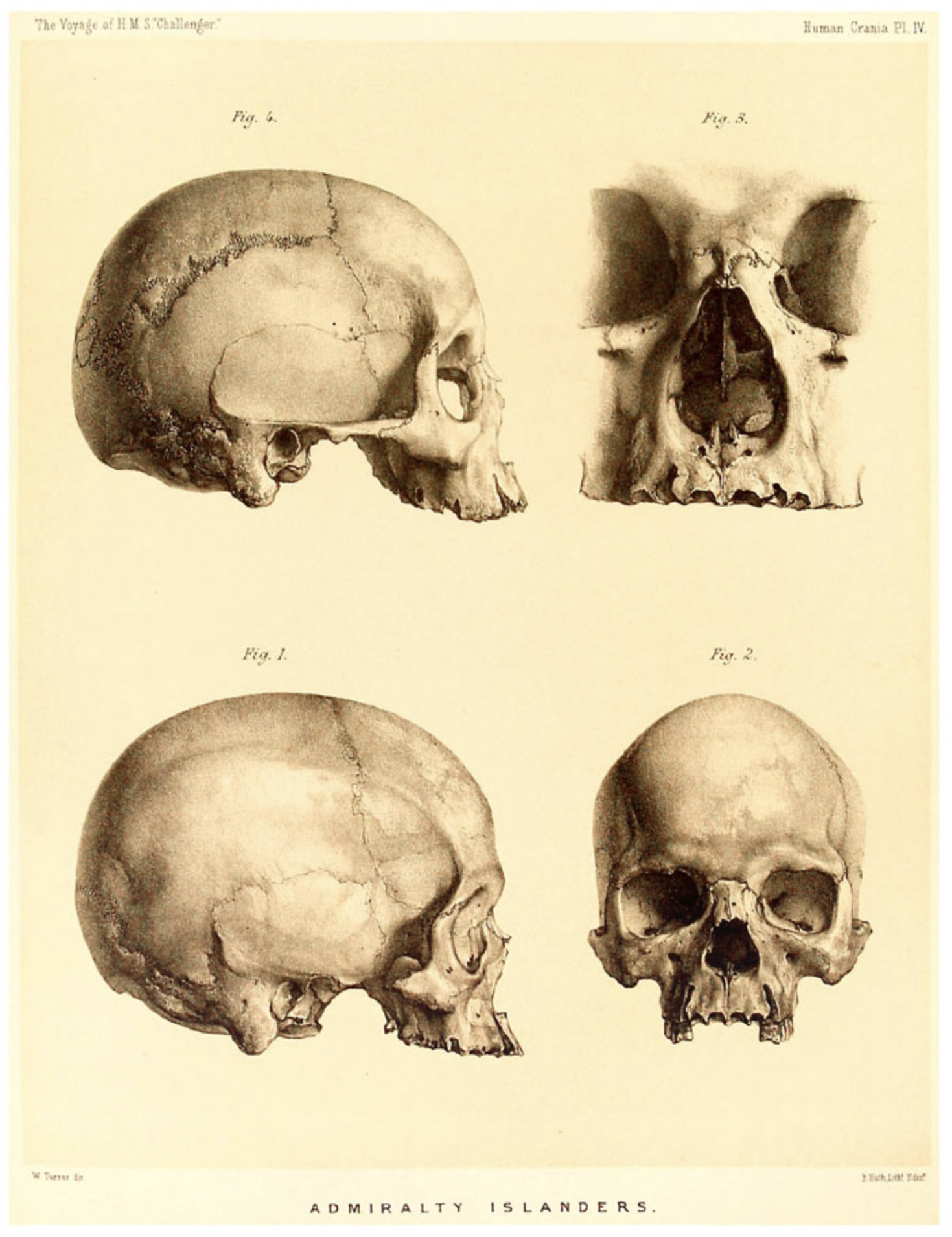

KFM: I will say that the people who have studied and encountered the ocean have a gaze. That is something I talk about in my research. From 1872 to 1876, the HMS Challenger, a warship, was repurposed for scientific exploration. It sailed around the world adhering, to some extent, to slave trade routes. The ship had a laboratory on board, and a group of scientists collected animal specimens. During the voyage, they also acquired a collection of human skulls—of nonwhite people, mostly—which they examined according to the disreputable science of phrenology, which tries to say something about intelligence based on the shape of the skull. So, of course, all the skulls from Africa and other places were coded as “less intelligent,” “less developed,” and so on. That’s considered the founding voyage of oceanography.

During a recent virtual conference on the Black Pacific, one of the questions I asked was about different approaches to the ocean, because I think, in the Western approach, the ocean is a space to be conquered. We fight on it. We claim territory. It’s used for commerce, obviously—the ultimate commerce that constructed modernity being the slave trade from the African continent. But in other cultures—Indigenous culture, Black culture—it’s not a conquering space. It’s a space that is generative. It’s Mother Earth, and it sustains you, and you also use it for pleasure—not that Western culture doesn’t use it for pleasure, because we do, but the approach is different. And sometimes, in terms of religion, it’s a beneficent Mami Wata. I always think of the ocean as having memory, but so much of what happens in the ocean is unseen. If the ocean has a gaze, we don’t have full access to it—though we do have access enough to know when we are affecting it in a negative way.

The lowest level of the ocean is called the hadal zone, named after Hades, and it was just assumed that there was no life down there because sunlight doesn’t penetrate beyond a certain point. Then scientists sent down photography equipment and found it was teeming with forms of life that were previously unknown—unseen and unknown. So, it’s sort of like the ocean’s gaze because it holds all this life, and we’re just scratching the surface of it and its processes.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Kathie Foley-Meyer is a mixed media artist whose work explores themes of interconnectedness, memory, visibility and transparency. She completed a PhD in Visual Studies at UC Irvine, where her dissertation project focused on the ocean memory of Black lives lost during the trade in human beings from the African continent. She received her MFA in the Writing Program in Critical Studies from California Institute of the Arts.

As an arts advocate, she served on the board of LACE (Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions) from 2011 to 2019, with the last three years as chair. She also served on the board of the Museum of Neon Art, and is part of the Advisory Committee for Fulcrum Arts.

Kathie was part of the art selection and art advisory committees for Metro Art for the Expo Metrorail Line, and has served on grant panels for the LA County Arts Commission. As an arts consultant she worked on CSR for a company in the global finance sector and has provided services to arts organizations serving Black communities in Los Angeles.

—

Title image: Kathie Foley-Meyer, tbbal no. 1, 2023. Mixed media print. Image courtesy the artist.

Archival images:

The illustrations depicting human crania are from Report on the human crania and other bones of the skeletons collected during the voyage of H. M. S. Challenger in the years 1873-1876 by Sir William Turner (London, 1884).

- The exhibition Descent and Transformation, Vol. 1: Voyages to the Americas ran from November 9 to December 21, 2024. [↩]

- Shades of L.A. is an archive of photographs representing the contemporary and historic diversity of families in Los Angeles. Images were chosen from family albums and include daily life, social organizations, work, personal and holiday celebrations, and migration and immigration activities. Made possible and accessible through the generous support of the Security Pacific National Bank, Sunlaw Cogeneration Partners, Photo Friends, California Council for the Humanities, the Ralph M. Parsons Foundation, and the John Randolph Haynes and Dora Haynes Foundation. [↩]

- This image was also included in Little Tokyo: One Hundred Years in Pictures by Ichiro Mike Murase, published by Visual Communications and the Asian American Studies Center, Los Angeles, 1983. [↩]